Underseas cables are vital to global economy

Undersea cables are a valuable commodity in the 21st century global communication environment. The undersea consortium is owned by various international companies such as ATT, and these companies provide high-speed broadband connectivity and capacity for large geographic areas that are important entities of trade and communications around the globe. If undersea cables were cut or disrupted outside of the U.S. territorial waters, even for a few hours, the capability of modern U.S warfare that encompasses battle space communications and awareness, protection, and the stability of the financial networks would be at risk.

Quicktabs: Arguments

As the amount of cable disruptions increases (i.e., more cables are cut), on the other hand, the amount of data traffic that is lost increases exponentially.33 For example, an analysis was done of possible disruptions of the cable lines connecting Europe and India.34 It found that although "India is fairly resilient in the case of one or two cable disruptions," nearly seventy percent of traffic to and from India would be lost with just three concurrent cable disruptions.35 Actual data exists that supports similar predictions.36 In 2006, an earthquake along the coast of Taiwan triggered undersea landslides and broke nine undersea cables.37 This event had repercussions extending beyond the country of Taiwan.38 Internet telecommunications linking Southeast Asia were seriously impaired.39 More than six hundred gigabits of capacity went offline, and trading of the Korean won temporarily stopped.40 Even a week after the quake, an Internet provider in Hong Kong publicly apologized for continued slow Internet speeds.41

As a result, companies, governments, and individuals can send and receive more data than ever before. In 1993, Internet users transmitted around 100 terabits of data in a year; today, they send about 150 terabits every second. And this number is expected to exceed 1,000 terabits by 2020, fueled in large part by the expansion of cellular networks in Africa, Asia, and the Middle East.

Nearly all that data will travel along the seabed. Imagine, then, how damaging a determined attack on undersea infrastructure could be. One need only consider the destruction possible from natural causes and inadvertent interference. In 2006, an undersea earthquake near Taiwan snapped nine cables. It took 11 ships 49 days to finish repairs, while China, Japan, the Philippines, Singapore, Taiwan, and Vietnam lost critical communication links, disrupting regional banking, markets, and trade. In 2007, Vietnamese fishermen seeking to salvage copper from a defunct coaxial cable pulled up active lines instead, disrupting Vietnam’s communications with Hong Kong and Thailand for nearly three months and requiring repairs that cost millions. Given the scarcity of equipment and personnel, it could take months, if not years, for the United States to recover from a large-scale, coordinated assault. Attackers wouldn’t even need to target U.S. assets, since U.S. traffic flows through more than a dozen other countries that serve as major hubs for the global undersea cable network.

Much of this infrastructure allows the global economy to function. Every day, SWIFT, the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication, transmits some 20 million messages to more than 8,000 banking organizations, security institutions, and corporate customers in nearly 200 countries, reconciling trillions of dollars’ worth of assets across global financial markets. Intercontinental Exchange, which operates a global network of currency exchanges and clearing-houses, typically processes over ten million contracts each day, covering the energy, commodity, financial, and equity derivatives markets. Without the undersea fiber-optic network, this type of electronic banking and commerce simply could not happen. And in the event that the cable system shut down, millions of transactions would be cut short.

The U.S. Department of Defense listed the world’s cable landing sites as among the most critical of infrastructures for the United States.183 Cable landing sites are concentrated in a few geographic areas due to high expense and economies of scale.184 According to one report, there are at least ten major cable chokepoints that exist globally.185 As observed by one commentator:

The most dangerous vulnerability is the aggregation of high-capacity bandwidth circuits into a small number of unprotected carrier hotels in which several hundred net- work operators interconnect their circuits in one non-secure building. These buildings often feed directly into the international undersea cable system. Security is often farcical. This lack of protection exists in several carrier hotels on transit points along the axis of the international telecommunications system that includes Dubai, Zurich, Frankfurt, London, New York, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Tokyo, Hong Kong and Singapore.186

Apart from cable landing sites, another vulnerability is the vast network of submarine cables on the seabed itself. Telecommunications companies “concentrate a large percentage of overall bandwidth in just a few major cable systems because new cable designs also incorporate tremendous capacity.”187 Cables also tend to be bundled together, “offering a potentially lucrative, consolidated target for sabotage.”188 If a bundle of cables are severed all at once, it could result in responders having little to no chance of restoring the connection by rerouting the traffic to mitigate the effects of the cut.189 Due to the unpredictable ocean environment, there are obvious challenges in actually carrying out an attack, however, a disruption could occur as a result of something as simple as dropping an anchor on a cable or sending a scuba diver down to physically cut them (all cable routes are publicly available).190 Further, one scholar has pointed out the possibility of nefarious elements using an Unmanned Undersea Vehicle (UUV) to attack cables.191

National economies now rely on undersea connectivity for a growing portion of their overall output. Today, essentially every consumer or commercial product contains commodities and parts drawn from dozens of separate countries in a “manufacturing chain” of subcomponent builders, product assemblers, suppliers, wholesalers, and retailers. These disparate players are able to seamlessly integrate their efforts using the Internet, enabling greater specialization and economies of scale within each step of the manufacturing process. This, in turn, promotes economic growth in countries that no longer have to either build an entire product domestically with great inefficiency or import it at high cost.

Global manufacturing chains and financial services are made possible by transoceanic cables, and more cable is being laid each year to meet the growing demand for bandwidth. The Asia Pacific Gateway cable, installed in 2014, transmits 55 terabytes of data per second (Tbps) – the equivalent of 100 computer hard drives – between East Asian countries from Malaysia to South Korea, funded in part by Facebook. Similarly, Google helped fund the installation of the FASTER cable between the United States and Japan, which will carry 60 Tbps, and is bankrolling a new 64 Tbps submarine cable between the United States and Brazil. Both content companies are hoping the new networks will increase their user rolls and reduce costs in underserved areas such as Southeast Asia, Latin America, and Africa. Data transmission to these regions with older cables can cost up to 10 times more than to Europe or Japan.

Many people around the world believe that their emails and phone messages are being sent through satellites. They are mistaken because satellites account for less than 5%.1 Global telecommunications development began about 150 years ago with the first commercial international submarine cable, laid between Dover, England and Calais, France in 1850. In 1858, the first trans-Atlantic telegraph cable linked London with the new world, via Newfoundland.2 The 143 words transmitted in 10 hours, replaced a one-way dispatch that would have previously taken about 12 days.3

In the last 25 years, there has been a stunning growth in undersea cables because of the communications revolution triggered by the internet. Undersea cables account for 95% of the world’s international voice and data traffic (Military, Government, Emergency Response, Air Traffic Control, Subway, Rail, and Port Traffic).4 Financial markets utilize undersea cables to transfer trillions of dollars every day. In 2004 alone, nine million messages and approximately $7.4 trillion a day was traded on cables transmitting data between 208 countries.5 As a result, submarine (undersea) cables are vital infrastructure to the global economy and the world's communication system.

Douglas Burnett, a legal expert on undersea cables notes that international banking institutions process over $ 1 trillion dollars per day via undersea cables. Any disruptions of these cables would severely impact global banking. Indeed, Stephen Malphrus, Chief of Staff to Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke, recently noted, “When communication networks go down, the financial services sector does not grind to a halt, rather it snaps to a halt.6 Even though there are hundreds of cables crossing the global seabed, there are just not enough undersea communication network redundancies available to handle the vast amount of bandwidth needed to keep global banking transactions in check.

Destruction of submarine cables can cripple the world economy to include the global financial market and/or Department of Defense (DoD). An example which reflects the importance of this strategic communication capability took place on December 26, 2006, when a powerful earthquake off Southern Taiwan cut 9 cables and took 11 repair ships 49 days to restore. The earthquake affected Internet links, financial markets, banking, airline bookings and general communications in China, Hong Kong, India, Singapore, Taiwan, Japan and the Philippines.7 When a cable loses service, it has a definite, but difficult impact to the global financial sector. The International Cable Protection Committee (ICPC) legal advisor estimates that interruptions of underwater fiber optics communications systems have a financial impact excess of $1.5 million per hour.8 These estimates target operators that utilize cable bandwidth for day-to-day operations and companies or government entities that own bandwidth on the disrupted cable.9

Undersea cables are a valuable commodity in the 21st century global communication environment. The undersea consortium is owned by various international companies such as ATT, and these companies provide high-speed broadband connectivity and capacity for large geographic areas that are important entities of trade and communications around the globe.41 For example, the U.S. Clearing House Interbank Payment System processes in excess of $1 trillion a day for investment companies, securities and commodities exchange organizations, banks, and other financial institutions from more than 22 countries.42 The majority of their transactions are transmitted via undersea cables. In addition, the Department of Defense’s (DoD’s) net-centric warfare and Global Information Grid rely on the same undersea cables that service the information and economic spheres.43 If undersea cables were cut or disrupted outside of the U.S. territorial waters, even for a few hours, the capability of modern U.S warfare that encompasses battle space communications and awareness, protection, and the stability of the financial networks would be at risk. As one analyst has noted, “the increase demand is being driven primarily from data traffic that is becoming an integral part of the everyday telecommunications infrastructure and has no boundaries.44

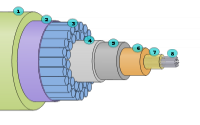

Submarine cables represent critical communications infrastructure, as they form the backbone of the Internet and global e-commerce. Such cables, typically consisting of optical fibers laid along the ocean floor in a bundle no larger than a garden hose, carry over 95 percent of transoceanic voice and data communication. U.S. telecom companies have worked rapidly to meet exploding consumer appetite for data, increasing the total circuit capacity of transoceanic cables landing in the U.S. by more than 1,000 fold since 1995.

There is no substitute for these underwater cables in case of damage. The earth’s satellites can carry no more than seven percent of U.S. international voice and data traffic. But worldwide, nearly 100 cable outages occur each year. The vast majority of cable outages are caused by bottom trawling fishing, dredging, and ship anchoring. Occasionally, cables are taken in an act of piracy, as occurred in 2007 when individuals in commercial vessels from Vietnam stole over 100 miles of cables on the high seas. Cable outages may disrupt governments, financial markets, and business operations and require costly repairs.

Pages

An underseas cable accident plunged the country of Yemen into a days-long internet outage, underscoring the fragility of the current internet infrastructure.

[ More ]

The U.S. and its NATO allies have warned that an uptick in Russian submarine activity near undersea fiber optic cables means Moscow may be plotting to disrupt or intercept sensitive or other critical internet communications in the event of a confrontation with the West.

[ More ]