Cable Vision

The author argues that "[i]t’s time to pay attention to security for undersea cables—crucial to global communications and commerce, and vital to our national interests."

Quicktabs: News

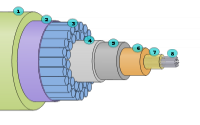

The importance of modern fiber-optic cables to the global economy and the Internet cannot be overstated. In the case of the United States, about 36 submarine cables, each the diameter of a garden hose, carry more than 95 percent of the nation’s international voice, data, and video communications.

Every day the Society for Worldwide Interbank Fi- nancial Telecommunications transmits 15 million mes- sages over cables to more than 8,300 banking organiza- tions, securities institutions, and corporate customers in 195 countries. The Continuous Linked Settlement Bank located in the United Kingdom is just one of the critical market infrastructures that rely on those transmissions, providing global settlement of 17 currencies having an average daily equivalent of approximately $3.9 trillion. Similarly, the U.S. Clearing House Interbank Payment System processes in excess of $1 trillion a day to more than 22 countries for investment companies, securities and commodities exchange organizations, banks, and other financial institutions.

The popular belief that international communications are carried largely by satellite is false. The tremendous volume of data carried on less expensive, modern fiber- optic submarine cables dwarfs the limited capacity of the higher-cost satellites. Additionally, the technical transmission delays and other quality limitations inher- ent in satellites make them marginal for continuous transmission of high-speed voice, video, and data traf- fic. If the cables connecting the United States to the world were cut, it is estimated that every single satellite in the sky combined could carry only 7 percent of the current total traffic volume.

Referring to the submarine cable networks, the Federal Reserve’s staff director for management, Ste- phen Malphrus, observed that “when the communication networks go down, the financial sector does not grind to a halt, it snaps to a halt.” The same can be said for most sectors enmeshed in the global economy through the Internet, including shipping, airlines, and manufacturing.

International treaties require states to enact laws providing for criminal sanctions against wrongdoers and vessels that injure international cables willfully or by culpable negligence.2 But compliance is poor.

Australia and New Zealand have modern and extremely effective deterrent laws that generally comply with the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). In both nations proactive monitoring of cables and effec- tive enforcement of domestic laws has essentially reduced cable faults to zero. But other countries, such as the United States and the United Kingdom, have telegraph-era stat- utes dating to the 1880s that are historical relics having virtually no practical utility.

In the United States, for example, the intentional destruction of an international submarine cable is subject to a ridiculously lenient maximum fine of $5,000 and a prison term of six months.3 The only known attempt to use the archaic law came in 1997, when the U.S. Coast Guard recommended to the U.S. attorney in Florida thathe skipper of a fishing vessel be prosecuted for willfully damaging the U.S.-Cuba cable. The attorney declined to prosecute, deeming the pursuit of a conviction carrying such a paltry penalty to be an inefficient use of his re- sources. Additionally, that sort of handicap for U.S. telecommunications companies is significantly compounded because the United States has not joined the 162 nations that are parties to UNCLOS. Thus there is no UNCLOS protection for their cables outside U.S. territorial seas.

While the United States justifiably can be criticized for allowing its domestic law protecting cables to sink into obsolescence, many nations have no laws whatsoever addressing damage to international cables—even though their economies depend on the critical global infrastructure.

That security gap should be of international concern for a number of reasons. The first successful hostile ac- tions by pirates and terrorists against active international cables already have occurred. In March 2007 Vietnamese pirates in multiple vessels carried out high-seas depredations on two active submarine cable systems, including the theft of optical amplifiers that rendered the systems inoperative for 79 days until re- placements could be manufactured.4 At the time, cable owners urgently pleaded with at least four nations for help in preventing ad- ditional attacks, only to learn that none of those governments had contingency plans for such action. Similar damage was inflicted on a newly laid cable in Indonesian archipelagic waters in 2010.

Submarine cables are legitimate targets of belligerents in war.5 The United States cut cables linking Spain to its colonies during the Spanish-American War.6 The first offensive action of Britain’s Royal Navy in World War I was cutting Germany’s international links to the rest of the world by severing its cables.7

But attacks on cables by terrorists are new. On 11 June 2010, terrorists in the Philippines successfully struck an international cable.8 It is naïve to assume that submarine- cable landing stations, cables, the cable ships, and the marine depots that maintain the systems will escape asym- metric terrorist acts.