Underseas Cables

Quicktabs: Keywords

That security gap should be of international concern for a number of reasons. The first successful hostile ac- tions by pirates and terrorists against active international cables already have occurred. In March 2007 Vietnamese pirates in multiple vessels carried out high-seas depredations on two active submarine cable systems, including the theft of optical amplifiers that rendered the systems inoperative for 79 days until re- placements could be manufactured.4 At the time, cable owners urgently pleaded with at least four nations for help in preventing ad- ditional attacks, only to learn that none of those governments had contingency plans for such action. Similar damage was inflicted on a newly laid cable in Indonesian archipelagic waters in 2010.

Submarine cables are legitimate targets of belligerents in war.5 The United States cut cables linking Spain to its colonies during the Spanish-American War.6 The first offensive action of Britain’s Royal Navy in World War I was cutting Germany’s international links to the rest of the world by severing its cables.7

But attacks on cables by terrorists are new. On 11 June 2010, terrorists in the Philippines successfully struck an international cable.8 It is naïve to assume that submarine- cable landing stations, cables, the cable ships, and the marine depots that maintain the systems will escape asym- metric terrorist acts.

As the amount of cable disruptions increases (i.e., more cables are cut), on the other hand, the amount of data traffic that is lost increases exponentially.33 For example, an analysis was done of possible disruptions of the cable lines connecting Europe and India.34 It found that although "India is fairly resilient in the case of one or two cable disruptions," nearly seventy percent of traffic to and from India would be lost with just three concurrent cable disruptions.35 Actual data exists that supports similar predictions.36 In 2006, an earthquake along the coast of Taiwan triggered undersea landslides and broke nine undersea cables.37 This event had repercussions extending beyond the country of Taiwan.38 Internet telecommunications linking Southeast Asia were seriously impaired.39 More than six hundred gigabits of capacity went offline, and trading of the Korean won temporarily stopped.40 Even a week after the quake, an Internet provider in Hong Kong publicly apologized for continued slow Internet speeds.41

Undersea cable expert Douglas R. Burnett argues that "it is naYve to assume that submarine-cable landing stations, cables, the cable ships, and the marine depots that maintain the systems will escape asymmetric terrorist acts,"" and recent cases have proven that Burnett's concern is not unfounded. In 2007, "piracy was blamed in the theft of active submarine cables and equipment" off the coast of Vietnam." "In early 2008, over the course of just a few days, multiple cables were cut off the coasts of Egypt and Dubai," causing at least fourteen countries to lose a significant amount of data traffic." The "Maldives was entirely disconnectedfromtherestoftheworld."60 Theshorttimespanandclose proximity of these cuts raised suspicions of a deliberate attack.61 Most recently, in June 2010, terrorists in the Philippines struck an international cable.62 The public location of the cables and their lack of sophisticated armor or protection make them incredibly vulnerable to intentional attacks.

Perhaps even more troubling than the above-mentioned structural vulnerability of undersea cables is the lack of security efforts and criminal sanctions by governments to protect undersea cables and deter future attacks. U.S. National Intelligence director James Clapper recently testified that cyber attacks, (by which he meant purely digital attacks like computer worms or viruses that can shut down the electrical grid or financial markets),69 are the nation's number one security priority.70 Clapper highlighted how much governments, utilities, and financial services rely on the Internet and therefore are vulnerable to cyber attack.71 Yet at the same time, protection of undersea cables (a critical infrastructure that supports the Internet) from physical attacks is sorely lacking. For example, in the United States, the willful destruction of an international submarine cable is punishable by a maximum of two years in prison and a mere $5,000 fine.72 This fine is hardly a deterrent, and is far out of proportion to the damage that such an act would cause. Furthermore, the United States has not joined the 162 countries that have signed onto the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).73 As a result, there are no UNCLOS security protections for U.S. undersea cables outside of U.S. waters.74 Only Australia and Singapore have created a single point of contact within their governments to address issues of undersea cable security and to coordinate with cable owners to combat hostile actions.75 On a worldwide level, no organization is responsible for undersea cables and there have been no international tests of cable defense systems.76 The maintenance and security of the cables is left to private trade organizations.77 Given the extent to which governments themselves rely on these cables,78 the current lack of a coherent undersea cable security strategy by governments must be remedied. The infrastructure itself is vulnerable, and governments like the United States are not yet taking adequate actions to protect it. It is not enough for governments like the United States to focus on digital attacks on Internet systems. They must also take action to protect the physical structure of the Internet.79

As a result, companies, governments, and individuals can send and receive more data than ever before. In 1993, Internet users transmitted around 100 terabits of data in a year; today, they send about 150 terabits every second. And this number is expected to exceed 1,000 terabits by 2020, fueled in large part by the expansion of cellular networks in Africa, Asia, and the Middle East.

Nearly all that data will travel along the seabed. Imagine, then, how damaging a determined attack on undersea infrastructure could be. One need only consider the destruction possible from natural causes and inadvertent interference. In 2006, an undersea earthquake near Taiwan snapped nine cables. It took 11 ships 49 days to finish repairs, while China, Japan, the Philippines, Singapore, Taiwan, and Vietnam lost critical communication links, disrupting regional banking, markets, and trade. In 2007, Vietnamese fishermen seeking to salvage copper from a defunct coaxial cable pulled up active lines instead, disrupting Vietnam’s communications with Hong Kong and Thailand for nearly three months and requiring repairs that cost millions. Given the scarcity of equipment and personnel, it could take months, if not years, for the United States to recover from a large-scale, coordinated assault. Attackers wouldn’t even need to target U.S. assets, since U.S. traffic flows through more than a dozen other countries that serve as major hubs for the global undersea cable network.

Much of this infrastructure allows the global economy to function. Every day, SWIFT, the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication, transmits some 20 million messages to more than 8,000 banking organizations, security institutions, and corporate customers in nearly 200 countries, reconciling trillions of dollars’ worth of assets across global financial markets. Intercontinental Exchange, which operates a global network of currency exchanges and clearing-houses, typically processes over ten million contracts each day, covering the energy, commodity, financial, and equity derivatives markets. Without the undersea fiber-optic network, this type of electronic banking and commerce simply could not happen. And in the event that the cable system shut down, millions of transactions would be cut short.

A major attack on deep-water drilling infrastructure could have many immediate effects, but two stand out. First, the environmental damage could be devastating. Residents around the Gulf of Mexico are still feeling the repercussions of the 2010 explosion on BP’s Deepwater Horizon rig, and the cleanup costs have already reached into the tens of billions. Yet Deepwater Horizon was only one of thousands of production platforms and drilling rigs in the Gulf of Mexico, many of which belong to vast networks of undersea wells, pumps, and valves connected by thousands of miles of pipeline.

Second, an attack could cause a major disruption in global energy supplies. About one-third of global oil production now occurs offshore, with the largest fields in the Persian Gulf and the Caspian Sea. Onshore facilities along the Gulf Coast that are connected to sea-based ports by submarine pipelines account for over 40 percent of total U.S. oil-refining capacity and over 30 percent of U.S. natural-gas-processing capacity. Both in the United States and elsewhere, oil companies have increasingly ventured into deep and ultradeep water (greater than 1,000 and 5,000 feet, respectively). Over the past decade, global investment in offshore oil and gas infrastructure has steadily increased, from about $100 billion to over $300 billion annually. The estimated volume of newly discovered oil and gas reserves in deep water now exceeds that onshore and in shallow water. And by 2035, forecasts suggest, deep-water wells will account for 11 percent of total global production, up from six percent in 2013.

From a global and national security perspective, submarine communications cables also play an essential role. For example, “a major portion of the [U.S. Department of Defense] data traveling on undersea cables is unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) video, essential for war preparation.”49 As one scholar observed, “without ensured cable connectivity, the future of modern warfare is in jeopardy.”50 A further example of the importance of cables to the military is the development of the Global Information Grid (GiG) by the U.S. Department of Defense.51 The GiG is the “globally, interconnected, end-to-end set of infor- mation capabilities for collecting, processing, storing, disseminating and managing information on demand to warfighters, policy makers and support personnel.”52 The Grid utilizes portions of the international telecommunications systems and has been described as a “global network that can be used to control a global battlespace.”53

The U.S. Department of Defense listed the world’s cable landing sites as among the most critical of infrastructures for the United States.183 Cable landing sites are concentrated in a few geographic areas due to high expense and economies of scale.184 According to one report, there are at least ten major cable chokepoints that exist globally.185 As observed by one commentator:

The most dangerous vulnerability is the aggregation of high-capacity bandwidth circuits into a small number of unprotected carrier hotels in which several hundred net- work operators interconnect their circuits in one non-secure building. These buildings often feed directly into the international undersea cable system. Security is often farcical. This lack of protection exists in several carrier hotels on transit points along the axis of the international telecommunications system that includes Dubai, Zurich, Frankfurt, London, New York, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Tokyo, Hong Kong and Singapore.186

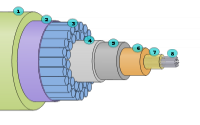

Apart from cable landing sites, another vulnerability is the vast network of submarine cables on the seabed itself. Telecommunications companies “concentrate a large percentage of overall bandwidth in just a few major cable systems because new cable designs also incorporate tremendous capacity.”187 Cables also tend to be bundled together, “offering a potentially lucrative, consolidated target for sabotage.”188 If a bundle of cables are severed all at once, it could result in responders having little to no chance of restoring the connection by rerouting the traffic to mitigate the effects of the cut.189 Due to the unpredictable ocean environment, there are obvious challenges in actually carrying out an attack, however, a disruption could occur as a result of something as simple as dropping an anchor on a cable or sending a scuba diver down to physically cut them (all cable routes are publicly available).190 Further, one scholar has pointed out the possibility of nefarious elements using an Unmanned Undersea Vehicle (UUV) to attack cables.191

In November 2007, there was a report of the intentional sabotage of a cable in Bangladesh, which resulted in a total loss of communications for at least one week causing a loss of 1.05 million U.S. dollars in revenue by the Bangladesh Telegraph and Telephone Board.201 In addition, there have also been reports of cable theft in Jamaica in 2008 where Cable and Wireless Jamaica lost 1.5 million dollars,202 and a 2010 attack by separatists against the beach manhole con- nection of a submarine cable system linking the Philippines with Japan.203 In March 2013, it was reported that 16 tons of submarine cables laid on the sea- bed between Bangka Island and the Riau Islands in Indonesia were stolen.204 Perhaps more disturbingly is an incident that occurred in April 2013, when there were interruptions on multiple undersea communications cables that link Europe to the Middle East and Asia including I-ME-WE, TE North, EIG and SEA-ME-WE 3.205 While initially chalked up to dragging ship anchors, the Egyptian coast guard caught three divers trying to cut the SEA-ME-WE-4 near Alexandria, although the motives of such an act remain unknown.206