Underseas Cables

Quicktabs: Keywords

Ambiguity, coupled with our extreme reliance on undersea infrastructure, was on display in late January and early February 2008. Four undersea telecommunication cables were mysteriously cut within the course of two days, crippling Internet access across wide swaths of the Middle East and India.59 Two cable breaks were in the Mediterranean--one near Alexandria, Egypt, and the other in the waters off Marseille, France.60 The third break was thirty-five miles off the coast of Dubai and the fourth was along a cable linking the United Arab Emirates to Qatar.61 Most telecommunication experts and operators deemed sabotage unlikely, believing instead that ship anchors had severed the cables when heavy storms swept through the region.62 Nevertheless, the Egyptian Ministry of Communications refuted the presence of any ships near the Mediterranean cable cuts.63 Moreover, the improbable incidence of four cuts in 48 hours fueled speculation about military involvement.64 Sabotage theorists seized on reports of stifled Internet traffic through Iran,65 while traffic to Israel, Lebanon and Iraq was apparently immune from chaos.66 At the very least, this episode highlights how relatively small damage to undersea cables can instantly affect millions of people, and how a stealthy underwater attack- ambiguous and non-attributive in nature-could deal such a crippling blow.

States and private owners may assert claims or jurisdiction over undersea infrastructure on various grounds. States may assert claims on behalf of injured parties incorporated or present within their jurisdiction. Pipeline and cable owners, meanwhile, have direct recourse to traditional admiralty remedies in national courts that retain jurisdiction over the vessels and persons responsible for undersea depredations.82 However, under international law, a corporate person whose property has been damaged possesses rights that are merely derivative of the rights of its state of nationality. As a broad based source of international maritime rights and obligations, the 1982 Convention on the Law of the Sea (LOSC, or colloquially, the "Constitution of the Oceans") 84 currently contains the most robust provisions for claims asserted by either affected states or subsea proprietors.

The legal status of pipelines in waters beyond national urisdiction has been associated with the status of submarine cables. Without the LOSC, two operative treaties for international cables exist: the 1884 International Convention for Protection of Submarine Telegraph Cables (Cable Convention), and the 1958 Geneva Convention on the High Seas.87 These treaties deal with laying and repairing cables on the high seas-not in Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ) and upon the continental shelf8.8 Moreover, they do not afford commercial owners significant deterrence against depredations.

Even if the LOSC fails to classify subsea attack as piracy with full recourse to the convention's robust remedies, it does proscribe depredations against cables and pipelines under the high seas and the EEZ. As discussed above, the traditional rights of U.S. cable owners outside of territorial waters have been victimized by a dearth of enforcing legislation. By delaying the ratification of the LOSC, this lack of effective prosecution persists.157

World telecom companies rightly believe that the LOSC facilitates more confident investments than simply operating under the bare aegis of customary international law.158 Simply defending against customary law encroachments does not deter underwater attack, but with U.S. ratification, U.S. telecom and energy companies as well as the U.S. Navy could seek greater government assistance in enforcing propert rights and undersea infrastructure security outside of territorial seas.159 Moreover, all U.S. stakeholders would have a firmer basis in holding other states responsible for their loss.160

As a condition for ratifying LOSC, the United States could take the helm in updating the convention to meet new military and commercial paradigms since it was first drafted three decades ago. Such revisions may include one or more of the following proposals.

Submarine cables and pipelines are vulnerable assets in the global commons.182 Their protection from undersea attack is a real prescriptive and enforcement challenge because of our extreme reliance on this critical infrastructure; its multi-jurisdictional span beyond territorial seas; the availability of precise locational coordinates; the opaque environment below the waterline; and the accessibility to commercial-grade vehicles that can exploit this environment and inflict disproportionate harm.

The opaque environment and the accessibility to UUVs set this challenge apart from challenges above the water's surface to flagged vessels and platforms. As with cyber threats, this necessitates an effective deterrence policy to compensate for an inability to pinpoint suspected culprits. Not only do legal shortcomings in jurisdiction and security enforcement float above the surface, but arguably more sinister shortcomings lurk below. These threats also require an even more delicate balance between disclosure and secrecy, and between freedom ofnavigation and reasonable restraints for collective security.

In the end, whatever vigor is applied towards cyber security, and whatever balance is struck for internet freedoms should be matched by securing the very cables that transport this life-blood of commerce. Likewise, investment in energy independence should correspond to the security of the very arteries that enable and spur offshore energy exploration.

Currently, the main concerns relating to submarine cables are in the perspective of multiple ocean use introduced by UNCLOS. The conflicts between cables and other ocean uses, the overlapping of maritime zones, the legality of exclusion zones around cables, compensation for lost or damaged fishing gear due to cable interactions, legal liability for damaging cables, and unclear jurisdiction and interdepartmental coordination in the cable licensing and regulatory processes are only some of the potential conflicts to be resolved by States.

In particular, with regard to the laying of submarine cables, doubts can be also expressed about the interaction between the interest of coastal States to regulate their maritime spaces and the possibility to lay submarine cables by other States or individuals. Furthermore, in the maritime zones outside of the sovereignty of coastal States, the freedom to lay cable is often opposed to environmental issues as well as the interest to have safe navigation. Laying activities may interfere with the repair of submarine cables as well as navigation for fishing. In addition to this, coastal States often impose taxes on cables laid on the continental shelf or other excessive regulations.24

This lack of precision in the regulations for the laying of submarine cables leads also to enhance the weakness of the measures of protection available in the field.

As previously stated,25 given the importance of submarine cables to the world economy and to all States, additional measures are necessary to protect cables. The majority of the cable damages are caused by human intervention, but there is no obligation under the UNCLOS on coastal States to adopt laws and regulations to protect submarine cables in the territorial sea. Moreover, even if Article 113 UNCLOS requires States to establish rules on the breaking or injury of cables in the high seas or EEZ by their nationals or by a ship flying their flag, if such break was done wilfully or with negligence, this provision is inadequate, as there is no countermeasure if States do not implement it. Furthermore, it does not deal adequately with the threat as well as theft of cables by terrorists or other voluntary acts.

In conclusion, these interactions and potential conflicts in the regime applicable to submarine cables regime make further ground arise for the integrated planning and management of activities in ocean and coastal areas.

The scholarship has repeatedly affirmed that such a cooperation and integration of different interests would be best achieved by means of the elaboration of a new international convention. However, it has to be pointed out that disruptions to the integrity of submarine cable systems potentially cost cable companies millions of dollars in repairs and lost revenues from e- commerce and telecommunications.29 In this perspective, rather then spending efforts to negotiate a new Convention on submarine cables, a solution – at least a partial one – can be represented by increasing the cooperation between all actors involved (privates and States) by means of BITs. This would help minimizing the risks of interferences and protect the interests of all the parties involved. As South-East Asia currently represents the most-relevant market for the lay of submarine cables, particular attention in the following analysis will be given to the BITs practice in the region.

As previously stated,61 [bilateral investment treaties] BITs can only partially solve the problems currently arising in the regime applicable to submarine cables. That is the reason why BITs have been referred to in this article as a “complementary” regime rather than a “substitutive” one. In fact, there are certain areas in which BITs cannot represent a solution. Reference is made in particular to the problem of intentional acts by terrorists aimed at damaging the cables, and issues related to cables laid down outside the sovereign areas of States (i.e. the High Seas). With regard to the former, the matter would be better addressed by international criminal law. BITs can establish the liability of the host State in case due diligence is not exercised in the protection of the cables. However, international terrorism is something beyond the control of States, and definitely something that can hardly be faced just by applying the ‘due diligence’ required by the standards of protection of investment law. With regard to the lay of submarine cables outside the sovereignty of States, it is evident that the lay of submarine cables in these areas cannot be regulated by BITs. Host States cannot be subject to obligations on areas on which they lack sovereignty.

The inadequacy of the regime provided by the law of the sea to effectively protect submarine cables, the relevance of which in national economies increases as time goes by, is hardly questionable. The UNCLOS, in particular, is a ‘constitutional’ convention, one that needs other instruments to be put in place in order to ensure the effectiveness of most of its provisions. As stated beforehand, BITs can provide only a partial solution to the problem – in other words, they can represent a solution only in those areas where coastal States exercise their sovereignty. In the high seas and in those areas where the sovereignty of a State is limited by the rights and duties of other States, BITs clearly cannot be a suitable solution. However, BITs and investment law in general can nonetheless represent a model worth following to fill the remaining lacunae of the law of the sea in the regime applicable to submarine cables. The lesson to be learned from investment law is that the multilateral approach is not necessarily the most appropriate. In investment law, the bilateral approach has been proven as successful as it allows each State to pursue their interest at the local level by negotiating the level of protection they deem appropriate in a particular State or region for their nationals. BITs could be a suitable instrument to reach effective and constant protection for submarine cables. Alternatively, bilateral or small multilateral treaties could help to solve once and for all the problem of the current inadequacy of the law of the sea in terms of protection of submarine cables.

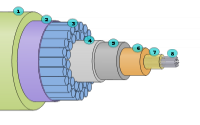

Over 70% of our country's international telecom traffic, which includes voice, data, and video, is carried on these cables, each of which is only about the diameter of a garden hose. Not counting Canada and Mexico, over 90% of the country's international voice, video, Internet, and data communications are carried on these cables. The disproportionate importance of these cables to the nation's communication infrastructure can be seen by the fact that if all of these cables were suddenly cut, only 7% of the United States traffic could be restored using every single satellite in the sky. Modern fiber optic cables are the lifeblood of the world's economy, carrying almost 100% of global Internet communication. This underscores the revolutionary5 capacity of modern fiber optic submarine cables. By any standard, they constitute critical infrastructure to the United States, and indeed the world.