Russia

Quicktabs: Keywords

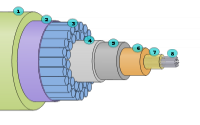

Russian submarines and spy ships are aggressively operating near the vital undersea cables that carry almost all global Internet communications, raising concerns among some American military and intelligence officials that the Russians might be planning to attack those lines in times of tension or conflict.

[ More ]

A resurgent Russian Navy is creating an "arc of steel" meant to challenge and confront NATO, a top US naval officer warned Tuesday.

[ More ]

The author argues that Russia's recent moves in the Arctic are bluster, aimed at distracting its public from its war in Ukraine and its failing economy.

[ More ]

The author argues that as the economic basis for Russia's expansion into the Arctic evaporates, the real motive -- to shore up domestic confidence in a failing economy wrought by sanctions -- becomes more apparent.

[ More ]

The author argues that Russia's Arctic adventures are more about maintaining Putin's standing at home while the country is stuck in Ukraine and battered by global energy trends.

[ More ]

The Editorial board argues that another reason for the U.S. to ratify UNCLOS is that it would give it more ability to challenge Russia's military expansion into the Arctic.

[ More ]

Russia has submitted its bid for vast territories in the Arctic to the United Nations, the Foreign Ministry said Tuesday. The ministry said in a statement that Russia is claiming 1.2 million square kilometers (over 463,000 square miles) of Artic sea shelf extending more than 350 nautical miles (about 650 kilometers) from the shore.

[ More ]

Republican U.S. Sen. John McCain of Arizona said that Russia has become a "national security issue" for the U.S. in an interview Friday with Politico's Morning Defense team. His comments were made ahead of a congressional delegation trip he has been planning to the Arctic as a response to a rapidly growing Russian military presence off the coast of Northern Europe.

[ More ]

The author argues that the U.S., Canada, and Russia would all benefit economically and strategically from greater cooperating together to establish safe, secure and reliable Arctic shipping.

[ More ]Pages

As a maritime state with interests in sustaining freedom of navigation on a global stage and in maintaining safety and security in its offshore waters, Russia in the twenty-first century will increasingly share interests long held by the United States and other ocean powers. Russia’s interests in its Arctic will foster a maritime policy that embraces coastal resource management and freedom of international navigation, though likely with a greater emphasis on offshoresovereignty and less on distant-water power projection. Strategic security policy will be a continuation of past and current policy, the U.S.-Russian maritime boundary is already resolved de facto (pending official approval of the boundary treaty by the Russian Duma), and current and potential territorial disputes between Russia and U.S. allies Norway, Denmark, and Canada are likely to be resolved through peaceful means. The United States and Russia also have an agreement that maritime-boundary and navigation disputes will be resolved diplomatically rather than by resort to arms.32 The conflicts that do arise will be focused on matters of commercial navigation, boundary delimitation, fisheries management, energy development, environmental protection, and ocean science, all the subjects of international diplomacy and regulatory enforcement rather than warfare.

The opening of the Arctic in the twenty-first century will give Russia the oppor- tunity to develop and grow as a maritime power, first in the Arctic and eventually wherever its merchant fleet carries Russian goods and returns with foreign products. This transformation of the threatening “heartland” of Mackinder and Spykman into a member of the maritime powers will require extensive effort to bring the new maritime Russia into the collaborations and partnerships of other oceangoing states. Commitment to the rule of law, shared Arctic domain awareness, joint security and safety operations, and collaboration in developing policies for the future can maintain the Arctic as a region of peace even while the coastal states maintain naval and law enforcement capabilities in the region.

The best course is to address Russia’s evolving maritime role with an Arctic regional maritime partnership based on the model of the Global Maritime Partnership initiative, expanded to address civilian interests in climate, resources, science, and conservation. The American objective should be to work collab- oratively to resolve disputes over continental shelf and fishery claims, negotiate a regional high-seas fisheries management plan, develop a regional Arctic maritime transportation plan, and coordinate security and safety policies on the ocean and ice surface and in the air, in line with the U.S. Arctic Policy and the sea services’ “Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Seapower."

Russia’s Arctic encompasses the northern seas, islands, continental shelf, and the coast of the Eurasian continent; in addition, it is closely linked to the vast watershed that flows to the sea. The Arctic coast of Russia spans from its border with Norway on the Kola Peninsula eastward to the Bering Strait. Along the coast is a wide continental shelf, running eastward from the Barents Sea in the west to the Kara Sea, the Laptev Sea, the East Siberian Sea, and the Chukchi Sea. Of these seas, only the Barents is largely ice-free throughout the year, a result of the Gulf Stream returning there to the Arctic. The continental shelf extends northward far beyond the two-hundred-nautical-mile exclusive economic zone (EEZ). When free of ice, the coastline along the Arctic extends almost forty thousand kilometers (including the coasts of the northern islands), which must be patrolled and protected. The Russian Arctic coast drains a watershed of thir- teen million square kilometers, equal to about three-quarters of the total land area of Russia and an area larger than any country on earth save Russia itself.

Russia has long been a major producer of oil and gas from land-based re- sources. Now the resources of the Arctic continental shelf are drawing increasing attention. Deposits in the Barents Sea are already being developed, with oth- er known deposits in both the Barents and the Kara seas being eyed for future exploitation. Still more energy resources are awaiting discovery. In 2008, the U.S. Geological Survey, estimating the as-yet-undiscovered resources of oil and gas in the Arctic, projected over 60 percent of the total resources (equivalent to about 412 billion barrels of oil) to be located in Russian territory, with all but a very small percentage on shore or inside the EEZ.6 The area of greatest poten- tial is in the Kara Sea basin, with smaller, yet still respectable, prospects in the Laptev and East Siberian seas.

In defense and protection of the border and resource areas, Russia continues to bolster military presence and capability in the Arctic. In addition to the Northern Fleet, whose naval military capabilities run the full gamut of surface and subsurface operations, Moscow has created the Federal Security Service Coastal Border Guard.67 Additional activities in the border and coastal areas include development of control infrastructure and equipment upgrades for the border guard, implementation of an integrated oceanic monitoring system for surface vessels, and a number of equipment and weapons testing and deployment initiatives.68 Many of these initiatives demonstrate presence and resolve, such as the 2007 launch of cruise missiles over the Arctic, additional Northern Fleet exercises in 2008, and the resumption of Arctic aerial and surface patrols not seen since the end of the Cold War.69 While many of these actions may appear provocative, Russia has also asserted its commitment to working within the framework of international law, partici- pated actively in the Arctic Council and other international bodies, and expressed interest in partnership in the region, particularly in the area of SAR.70 In the aggregate, Russia emerges as among the most prepared of Arctic nations for the opportunities available and may well be poised to gain early regional commercial and military supremacy with the goal of similar successes in the international political arena.71 Russian commitment to mul- tilateral venues, along with the demonstrated attitudes of other Arctic nations, presents the opportunity for U.S. partnership in the region.

Both Canada and the Russian Federation have enacted regulations that the United States believes amount to unwarranted restrictions on the right of transit passage. Canada, for example, imposed a mandatory ship reporting and vessel traffic service system (NORDREG) that governs transit through the Northwest Passage.29 NORDREG covers Canada’s EEZ and the several Northwest Passage routes in the Canadian Arctic Archipelago.30 Canada specifically cites UNCLOS Article 234 to justify NORDREG, asserting that the reporting requirements are to prevent and reduce marine pollution from vessels in the delicate Arctic waters.31 Similarly, the Russian Federation has historically limited transit passage in the Northern Sea Route,32 using UNCLOS Article 234 to justify the limitations,33 and has recently implemented more extensive unilateral regulations to ensure shipping safety and environmental protection.34 With receding amounts of ice for significant portions of the year, whether the Northwest Passage or the Northern Sea Route meets Article 234’s climatic requirements for ice- covered areas is debatable.35

Under UNCLOS, coastal states seeking to prescribe sea-lanes and traffic separation schemes in straits used for international navigation must receive approval by a “competent international organization” prior to adoption.36 The International Maritime Organization (IMO) fills this role. The United States is working with other Arctic nations through the IMO to create a mandatory “Polar Code” that will cover all matters relevant to ships operating in both Arctic waters and the waters surrounding Antarctica.37 The IMO recently announced that the Polar Code will be operational as early as 2015 and will be implemented by 2016.38 The extent to which the Polar Code reconciles Russian and Canadian interests in regulating the Northern Sea Route and Northwest Passage with freedom of navigation interests will be critical.

The world is at a precipice of a potential new cold war in the Arctic between Russia and the NATO Arctic nations. Russia is in a position to win it. The number of icebreaking hulls a country operates is the simplest and most tangible measure that can be used to judge its ability to conduct northern operations. The United States has a total of four diesel-powered icebreakers (one of which is out of service for this year) whereas the Russians have 14.51 Of the 14, seven are nuclear-powered--capable of cutting through nine feet of ice without even slowing down. In comparison, the U.S. icebreakers can only make it through six feet of ice at a constant speed.52 Even China and South Korea, non-Arctic nations, have icebreakers in preparation for regional access.53

In addition to greater Arctic naval power, the Russians also have a superior support infrastructure. The Soviet Union, in sustaining the Northern Sea Route and oil development in the Barents Sea, invested tremendous capital in developing a robust infrastructure of rail lines and river transport services. It maintained this infrastructure by offering state workers huge subsidies and inflated wages. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, and the loss of state jobs, the region experienced a significant reduction in population. However, the Russian North still has a fully functioning infrastructure in place.54 Meanwhile, the North American presence is ―naked and unguarded.55

Russia intends to use these weaknesses along with divisions among the NATO members to increase its power in the region. According to a leading Russian economic journal, ―...Russia’s main task is to prevent the opposition forming a united front. Russia must take advantage of the differences that exist [between NATO states]."56 Moreover, a prominent Russian Navy journal acknowledged that an increase in regional militarization could increase the possibility for local military conflict. ―Even if the likelihood of a major war is now small, the possibility of a series of local maritime conflicts aimed at gaining access to and control over Russian maritime resources, primarily hydrocarbons, is entirely likely."57

Conflict in the region, however, is not inevitable. Among the NATO allies, especially, there have been plenty of diplomatic successes to resolve differences. All the parties within the region have shown a willingness to work within the constraints of international law. Even Russia, despite its flag-planting antics, has accepted those constraints. In discussing Russia’s position on Arctic policy, its Ministry of Foreign Affairs released the following press statement, ―Russia strictly abides by the principles and norms of international law and firmly intends to act within the framework of existing international treaties and mechanisms. As was pointed out in the joint declaration of the ministerial meeting of the five Arctic coastal states held in Ilulissat, Greenland, this past May, these states, including Russia, are committed to the existing international legal framework that applies to the Arctic Ocean and to the orderly settlement of any possible overlapping claims.59 It is only in the Arctic areas where international law has failed that conflicts are escalating. Consequently, the United States must seek a way to bolster international law in order to provide stability in the region. To this end, U.S. Arctic policy must be guided by the following six steps.

If the U.S. Senate ratifies the Convention on the Law of the Sea of 1982, Russia will not witness any significant changes in bilateral relations in the Arctic. It is obvious that the U.S. intends to apply the Convention only when it coincides with its national interests. Potential conflicts will be resolved through bilateral negotiations rather than UNCLOS provisions directly.

Since the Convention does not oblige all contentious issues to be decided within its rules and institutions, the United States can either appeal to precedent or refuse to discuss an inconvenient problem in terms of the Convention. Apparently, some Russian experts underestimate the fact that under international law, common law prevails over codified law. This allows the U.S. to bypass the Convention and is all the more reason to not consider it a universal source of law on Arctic issues.

In line with this logic, experts from the Ministry of Defense and the Department of State submitted their official conclusions to the U.S. Senate in which they found that ratification would not impose any restrictions on the military.

Moreover if the Convention was ratified, the U.S. could appeal to the right of transit in territorial waters enshrined in the Convention as grounds for legal military presence not only in the Barents Sea, but also anywhere in the world. In case of complaints about the inadmissibility of covert presence or military activities in territorial waters, the United States could exercise the right of self-interpretation, challenging what is meant by military activities in the particular case (Article 298-1 of the Convention).

U.S. military activities cannot be a matter of contention within the framework of the Convention. Similarly, Russia will not receive any positive changes to the delimitation of the Bering Sea or defining the boundary line in the Chukchi Sea and beyond the exclusive economic zone towards the pole.

Thus, strategic environment and level of cooperation between Russia and the United States in the Arctic will be based on the state of their bilateral relations in general, and not on the U.S. decision of whether or not to ratify the UN Law of the Sea.

Meanwhile, Russia’s actions and rhetoric in the Arctic leave no room to deduce anything but a firm and committed intent on the part of its leadership to secure its claims. There have been scant, if any, peaceful actions undertaken by the Putin and Medvedev administrations to back up their peace-seeking rhetoric. Calls for diplomatic resolution of territorial disputes in the Arctic and for working “within existing international agreements and mechanisms” have only been operationalized through agreements to cooperate on search and rescue efforts and on (competitive) scientific exploration and research for submission to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS), a forum that has no binding authority to settle such disputes. All the while, however, Russia’s ambitious militarization of the Arctic has been clearly reinforced with explicit rhetoric proclaiming its intent to defend its national security interests. For Russia, the natural resources in the Arctic are a national security asset of strategic importance.

While it is undeniable that the Arctic states are using international institutions focused on Arctic issues, they appear to do so out of political convenience—not out of a commitment to peaceful cooperation. The participating nations all actively pursue a combined environmental and safety agenda with their partners through the Arctic Council. Its charter, however, explicitly bans the organization from discussing issues related to military security, a point reinforced by the Ilulissat Declaration of the five Arctic states: that is, no legal enforcement regime other than the UNCLOS is needed in the region.216

To that end, the UNCLOS does indeed provide conflict resolution mechanisms for territorial disputes and continental shelf claims, but Russia exempted itself from discussing such matters in UNCLOS fora when it acceded to the Convention. Moreover, while the United States continues to observe the UNCLOS as customary international law, it remains outside the Convention and is unable and unwilling to use its dispute resolution mechanisms.