Arctic Shipping

Due to steadily increasing warming, the Arctic region that was previously only passable with the help of icebreakers will soon be a major shipping route.

Quicktabs: Keywords

The author argues that the U.S., Canada, and Russia would all benefit economically and strategically from greater cooperating together to establish safe, secure and reliable Arctic shipping.

[ More ]

A new report from the International Council on Clean Transportation on air pollution from ships in the high Arctic warns of huge increases in air pollution from shipping.

[ More ]

As the Arctic ice melts, new shipping routes are opening up for tourism, mining and other commercial purposes, cutting journey times and fuel costs. And as Christopher Ware reports, a new danger arises - invasive alien species disrupting fragile Arctic ecosystems.

[ More ]

The U.S. military is looking for ways to expand operations in the vast waters of the Arctic as melting ice caps open sea lanes and other nations such as Russia compete for the lucrative oil and gas deposits. But the effort will take money and resources to fill the broad gaps in satellite and communications coverage, add deep-water ports and buy more ships that can withstand the frigid waters or break through the ice.

[ More ]

An ice-free Arctic will not bring more international shipping to Arctic maritime routes to and from China, the world’s largest market, according to a recent study by The Arctic Institute.

[ More ]

Russia's military said it planned to sail regular naval patrols along shipping lanes in its territory in the Arctic Ocean that opened to commercial vessels only in the last few years, as Arctic ice began melting at a record pace.

[ More ]

Icebreakers trawl the world's frozen seas, cutting a path for other ships in the harsh Arctic winter. Now, a new kind of ship that can drift sideways could make traffic - and trade - easier. Could the maritime technology change life in the extreme north?

[ More ]

Arctic shipping routes offer significant benefits, but also carry risks. If the Arctic Ocean is to become a new "Mediterranean Sea" - a middle ocean across which the world trades - the world's Asian and Arctic nations will have to work together.

[ More ]

Arctic shipping is set for a record year, as melting sea ice raises the prospect of an important new route for trade between Asia and Europe that shaves thousands of kilometres off the trip.

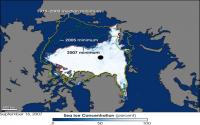

[ More ]Once long neglected in terms of governance and management, the Arctic is slowly attracting greater attention as a region in need of an effective legal regime following the observed and potential the impact of climate change in recent time.29 Science has provided overwhelming evidence of human-influenced Arctic climate change and the likelihood that the pace of change is accelerating. Scientists predict that the Arctic may be ice-free for the first time in recorded history by as early as 2013.30

An ice-free Arctic has two important implications. First, it will expose vast regions of seabed that are rich in natural resources, making extraction of these resources possible. It is estimated that about 30 per cent of undiscovered gas and 13 per cent of undiscovered oil can be found in the marine areas north of the Arctic Circle.31 According to the USGS estimates, Arctic region has the hydrocarbon reserves of 90 billion barrels of oil, 1,669 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, and 44 billion barrels of natural gas liquids.32 Second, an ice-free Arctic will open previously impassable shipping lanes, thereby, improving prospects for Arctic navigation. The most promising route, historically known as the "Northwest Passage" may become navigable, which would reduce the length of the voyage between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans by an astonishing 9000 kilometers.33

This will result in two separate but related problems. First, the increased value of the region due to commercial exploration and trade will prompt Arctic nations to rush to establish their claim over the region. In fact, many Arctic countries, pursuant to Article 76 of the UNCLOS, are preparing to submit requests to the United Nations Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf to establish the outer limits of their continental shelves.34 This has caused the spectre of rising tension over yet to be asserted maritime claims over the vast Arctic Ocean. The tension been further acerbated by the feasibility to extract the potential hydrocarbon resources in the Arctic seabed. The receding polar ice cap has ignited the competition for the mineral rights in the Arctic seabed. The competition arises from the fact that the Arctic is ―the only place where a number of countries encircle an enclosed ocean,35 which gives numerous countries a valid claim for the same territory.36

Another key mission of the Coast Guard is to promote safe and secure international trade. The convention promotes freedom of navigation and overfight, by which international shipping and transportation fuel and supply the global economy. Some 90 percent of global trade tonnage, totaling more than $6 trillion in value including oil, iron ore, coal, grain, and other commodities, building materials, and manufactured goods, are transported by sea every year.7

Currently, little international trade travels through the Arctic, but this is changing and will continue to increase in the decades ahead as the ice cover continues to recede and marine transportation technology advances. Moreover, there is considerable destinational shipping even now, such as to bring critical supplies to the North Slope and Alaskan coastal villages, and to remove vast amounts of minerals from the treasure trove in the Brooks Range in northwestern Alaska.

By guaranteeing merchant vessels the right to navigate through international straights, archipelagic waters, and coastal waters, the provisions of the convention promote dynamic international trade. Free navigation reduces costs and eliminates delays that would occur if coastal states were able to impose various restrictions on navigational rights.

As a nation with global maritime interests, the United States has consistently viewed the UNCLOS provisions on freedom of navigation on the high seas and in exclusive economic zones (EEZs), “transit passage” through straits used for international navigation, and “innocent passage” through territorial seas as the convention’s essential core.12 Although UNCLOS’ navigation provisions were not designed with the Arctic in mind per se, the provisions are consistent with the United States’ interest in freedom of navigation in and through the Arctic.13

Although experts differ on the imminence and extent of regular Arctic transits, some scientific studies suggest that increasing temperatures will result in a seasonally ice-free Arctic as early as the 2030s.14 As the ice recedes, many expect the opening of more expeditious travel routes,15 with consequences for international security and commercial activities.16 In particular, two trans-Arctic routes are expected to become increasingly critical: the Northwest Passage and the Northern Sea Route.17

Increases in resource exploration result in increased navigation.53 In addition to transportation tied directly to oil exploration, the Arctic will also become a favored route for merchants.54

There are numerous reasons to take advantage of Arctic sea routes. Not only are they much shorter than alternate shipping routes, but they also allow companies to avoid the costs associated with utilizing canals and the threats of pirates in certain parts of the world.55 Though the trip may be economically efficient, it is still not entirely void of danger. Scientists predict that icebergs and other hazards will continue to persist well into the future, thus increasing the danger to voyages through the Arctic region.56

Regardless of oil spills, the animals living in the area will face changed circumstances. Ocean-bearing ships leave a significant amount of pollution behind simply by operating in the ocean.57 In 1999, 12.5 percent of all oceanic pollution resulted from the transportation of petroleum.58 Noise pollution is also a serious concern among environmentalists in the region.59 If species cannot effectively communicate, scientists argue, their interactions will be limited, resulting in a less diverse and less resilient marine ecosystem.60 Policymakers should consider this harm in relation to the special state of the Arctic ecosystem, which tends to be more sensitive to these types of external, human-caused factors.

In the past, the ice covering the Arctic Ocean has presented a significant barrier to human use. One commentator asserts that, if not for the ice, “the Arctic Ocean would undoubtedly be one of the busiest seas in the history of civilization, rivaling the . . . Mediterranean.”12 Currently, only coastal regions can be navigated, and even then only by ice-breaker ships during certain times of the year, which leaves the remainder of the ArcticOcean reachable only by submarine.13 However,as further advances are made in technology and in the development of ice-breaking equipment, these waterways may become accessible year-round.14 One result of an ice- free Arctic is the opening up of a new shipping route between Europe and Asia known historically as the Northwest Passage. Access to the Northwest Passage could cut five thousand miles—or up to a week of sailing time— off circumpolar sea voyages, as these ships must otherwise travel via the Panama Canal.15 It is important to consider, however, that though seasonal melting may make the region more accessible in some respects, such melting will also result in more icebergs, creating new hurdles to access.16

Finally, in the longer term, the gradual opening of Arctic waterways to commercial traffic on a seasonal basis by 2030 will increase the need for persistent and pervasive constabulary patrols by all Arctic nations in order to regulate this activity. Not only will more ice-capable patrol vessels be required, but so too will be a robust logistics infrastructure, to include basing, transportation, supply, and communications. This third window for conflict in the Arctic will probably occur in the 2030 to 2045 time frame. The increase in commercial traffic activity will heighten tensions in U.S.-Canadian relations if a political compromise on the status of the Northwest Passage has not been reached, keeping in mind that the ultimate status of Russia’s Northeast Passage would be likewise affected. As Canada is extremely sensitive to matters of Arctic sovereignty and Russia is are unlikely to welcome unrestricted movement through its backyard, it should be expected that the same nationalist sentiment that erupted in the Sino-Japanese row over the disputed Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands would likewise be manifest in these cases as well, leading to a quick, and potentially intense, confrontation involving the United States, Russia, and Canada.

The shipping shortcuts of the Northern Sea Route (over Eurasia) and the Northwest Passage (over North America) would cut existing oceanic transit times by days, saving shipping companies -- not to mention navies and smugglers -- thousands of miles in travel. The Northern Sea Route would reduce the sailing distance between Rotterdam and Yokohama from 11,200 nautical miles -- via the current route, through the Suez Canal -- to only 6,500 nautical miles, a savings of more than 40 percent. Likewise, the Northwest Passage would trim a voyage from Seattle to Rotterdam by 2,000 nautical miles, making it nearly 25 percent shorter than the current route, via the Panama Canal. Taking into account canal fees, fuel costs, and other variables that determine freight rates, these shortcuts could cut the cost of a single voyage by a large container ship by as much as 20 percent -- from approximately $17.5 million to $14 million -- saving the shipping industry billions of dollars a year. The savings would be even greater for the megaships that are unable to fit through the Panama and Suez Canals and so currently sail around the Cape of Good Hope and Cape Horn. Moreover, these Arctic routes would also allow commercial and military vessels to avoid sailing through politically unstable Middle Eastern waters and the pirate-infested South China Sea. An Iranian provocation in the Strait of Hormuz, such as the one that occurred in January, would be considered far less of a threat in an age of trans-Arctic shipping.

Arctic shipping could also dramatically affect global trade patterns. In 1969, oil companies sent the S.S. Manhattan through the Northwest Passage to test whether it was a viable route for moving Arctic oil to the Eastern Seaboard. The Manhattan completed the voyage with the help of accompanying icebreakers, but oil companies soon deemed the route impractical and prohibitively expensive and opted instead for an Alaskan pipeline. But today such voyages are fast becoming economically feasible. As soon as marine insurers recalculate the risks involved in these voyages, trans-Arctic shipping will become commercially viable and begin on a large scale. In an age of just-in-time delivery, and with increasing fuel costs eating into the profits of shipping companies, reducing long-haul sailing distances by as much as 40 percent could usher in a new phase of globalization. Arctic routes would force further competition between the Panama and Suez Canals, thereby reducing current canal tolls; shipping chokepoints such as the Strait of Malacca would no longer dictate global shipping patterns; and Arctic seaways would allow for greater international economic integration. When the ice recedes enough, likely within this decade, a marine highway directly over the North Pole will materialize. Such a route, which would most likely run between Iceland and Alaska's Dutch Harbor, would connect shipping megaports in the North Atlantic with those in the North Pacific and radiate outward to other ports in a hub-and-spoke system. A fast lane is now under development between the Arctic port of Murmansk, in Russia, and the Hudson Bay port of Churchill, in Canada, which is connected to the North American rail network.

For example, the Arctic is a large area where multiple countries currently assert their jurisdiction. Countries have begun their expansion due to the effects of global warming.132 Because of rising ocean temperatures, ice caps have melted, causing areas that were once covered by ice to be accessible by ships.133 Countries have begun experimenting with new shipping routes and are actively searching for natural resources in the region.134 The search for natural resources has only just begun, as the resources are now accessible in the water.135 The ice caps that once served as a difficult obstacle to bypass are gradually disappearing, making access to the region much easier.

In particular, the United States has a large extended continental shelf in the Arctic, full of these untapped resources.136 The United States would be in a better position to argue disputes, such as one with Canada concerning the emerging neutral territory, if it acceded to UNCLOS.137 As Secretary Panetta noted:

Joining the Convention would maximize international recognition and acceptance of our substantial extended continental shelf claims in the Arctic. As we are the only Arctic nation that is not a party to the Convention, we are at a serious disadvantage in this respect. Accession would also secure our navigation and over-flight rights throughout the Arctic, and strengthen our arguments for freedom of navigation through the Northwest Passage and Northern Sea Route.138

Acceding to UNCLOS would help the United States solidify security over its jurisdiction in the Arctic, by providing both new trade routes and opportunities for deep seabed mining and the legal framework to support these activities.

First, the policy statement highlights the importance to our national security of navigation rights through international straits in the Northwest Passage over North America and the Northern Sea Route over Russia's northern border.33 Military and commercial navigation through those straits will become more important-and perhaps more contested-as the Arctic sea ice recedes and thins. Part III of the LOS Convention on straits used for international navigation includes twelve detailed articles that address the status of such straits, the right of transit passage, and the rights, responsibilities, and jurisdiction of states bordering on those straits. Although a right of transit passage through international states almost certainly ripened into a rule of customary law by the time the LOS Convention entered into force in 1994 (and before Canada became a party to the Convention in 2003), it seems certain that the customary law rule is not nearly as well defined as the articles in Part III of the Convention. Only as a party to the Convention would the United States be in a position to assert the full scope of the navigation rights set out in Part III of the Convention.