U.S. Navy's freedom of navigation is continually challenged by excessive claims

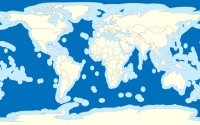

U.S. Naval forces are continually challenged by more than 100 illegal, excessive claims around the globe that adversely affect vital navigational and over-flight rights and freedoms. Accession to UNCLOS would give the U.S. Navy more tools to help rollback these violations.

Quicktabs: Arguments

[MYTH]: U.S. adherence to the Convention is not necessary because navigational freedoms are not threatened (and the only guarantee of free passage on the seas is the power of the U.S. Navy).15Sink the Law of the Sea Treaty — Bandow, Doug. — Cato Institute — Mar 15, 2004 [ More ]

But our navigational freedoms are indeed threatened. There are currently more than a hundred illegal, excessive claims affecting vital navigational and overflight rights and freedoms. The United States has utilized diplomatic and operational challenges to resist the excessive maritime claims of other countries that interfere with U.S. navigational rights as reflected in the Convention. But these operations entail a certain amount of risk—for example, the Black Sea bumping incident with the former Soviet Union in 1988. Being a party to the Convention would significantly enhance our efforts to roll back these claims by, among other things, putting the United States in a far stronger position to assert its rights and affording additional methods of resolving conflict.

Myth: Freedom of navigation is only challenged from "[t]he Russian navy [that] is rusting in port [and] China has yet to develop a blue water capability...." (14)Sink the Law of the Sea Treaty — Bandow, Doug. — Cato Institute — Mar 15, 2004 [ More ]

The implication here is that the principal challenge to navigational freedom emanates from a major power and that we do not have any particular national concerns about freedom of navigation. But the 1982 convention deals with the law of peace, not war or self-defense. Thus, this argument misses altogether the serious and insidious challenge, which, again, is what the convention is designed to deal with; these repeated efforts by coastal nations to control navigation, including those from U.S. allies and trading partners, have through time added up to death by a thousand pin-pricks. This is the so-called problem of "creeping jurisdiction" which remains the central struggle in preserving navigational freedom for a global maritime power. After years of effort, we have won in the convention a legal regime that supports our efforts to control this "creeping jurisdiction." To unilaterally disarm the United States from asserting what was won against illegal claimants is folly and undermines our national security.

Myth: U.S. adherence to the convention is not necessary because navigational freedoms are not threatened (and the only guarantee of free passage on the seas is the power of the U.S. Navy). Wrong--it is not true that our navigational freedoms are not threatened. There are more than 100 illegal, excessive claims around the globe that adversely affect vital navigational and over-flight rights and freedoms. The United States has utilized diplomatic and operational challenges to resist excessive maritime claims by other countries that interfere with U.S. navigational rights as reflected in the convention. On occasion, these operations have entailed a certain amount of risk (e.g., the Black Sea bumping incident with the former Soviet Union in 1988). Being a party to the convention would significantly enhance our efforts to roll back these claims by, among other things, putting the United States in a far stronger position to assert its rights, thus affording additional methods of resolving conflict and aligning expectations of behavior at sea.

Coastal states can also be expected to want more control of their off-shore waters and airspace for domestic security reasons.67 "Military Activities in the Exclusive Economic Zone: Preventing Uncertainty and Defusing Conflict ." California Western International Law Journal. Vol. 32. (2001-2001): 253-302. [ More (4 quotes) ] As technology advances, coastal states can reasonably be expected to seek a legal regime that makes it more difficult for foreign militaries to exploit advancements in the range and accuracy of weapons and intelligence-gathering inherent in manned and unmanned aerial, surface, and underwater vehicles, as well as over-the-horizon weaponry and specialized littoral platforms.

Moreover, the nature of threats such as terrorism; weapons of mass destruction; and arms, drugs, and human-trafficking encourage coastal states to extend surveillance and control beyond their territorial seas and in some cases even into others’ EEZs.68 In the aftermath of September 11, many nations, including the U.S., have increased surveillance of their coastal areas.69

To varying degrees and through various methods, coastal states have objected to military activities in their respective EEZs through the years. Whatever their historical weaknesses and current political rivalries, coastal states continue to share important interests and continue to face what Professor Bernard Oxman calls the “territorial temptation” to expand control over their off-shore waters.70

Moreover, numerous states question the United States’ very right to enforce navigational freedoms conferred by the Convention when it is not party to it. It is likely that U.S. accession would decrease the number of state claims inconsistent with international law and also decrease the number of freedom of navigation challenges the Navy would have to conduct.

The global demands on the Navy and Coast Guard come at a time when the size of the nation’s Fleets has shrunk to unprecedented low levels. As fewer and fewer U.S. ships are available to support U.S. and coalition interests worldwide, it is more imperative than ever that these ships be able to exercise the rights of innocent passage, transit passage, and archipelagic sea lanes passage without asking prior permission or providing prior notification to coastal states. Equally important is the right of warships to operate freely and conduct military activities in the exclusive economic zones of all nations. These are rights that are being increasingly challenged by coastal nations.

The proliferation of excessive coastal-state restrictions on military activities in the exclusive economic zone should be a growing concern to all maritime nations. Such restrictions are inconsistent with the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea and customary international law, and they erode the balance of interests that was carefully crafted during the nine-year negotiations that led to the adoption of UNCLOS. All nations must remain engaged, both domestically and internationally, in preserving operational flexibility and ensuring that the balance of interests reflected in UNCLOS is not eroded any further. The bottom line is that while UNCLOS grants coastal states sovereign rights for the purpose of exploring, exploiting, conserving, and managing the natural resources in the EEZs, it does not authorize them to interfere with legitimate military activities, which include much more than just navigation and overflight. Accordingly, U.S. warships, military aircraft and other sovereign immune ships and aircraft will continue to exercise their rights and freedoms in foreign EEZs, including China’s, in accordance with international law.

U.S. navigation on the high seas is affected by its non-ratification of UNCLOS III. For example, if a U.S. naval task force had to rush from the Persian Gulf to a crisis along the North Korean peninsula, it could be forced to detour 3,000 miles around Indonesia.234 Another example is the barring of U.S. tankers from the Strait of Hormuz-the strait in which most American foreign oil is shipped-by Iran.235 Finally, Russia could institute fishing trawlers off the coast of Alaska that would take millions of tons of salmon found in American waters.236 None of these things would be possible if the United States ratifies UNCLOS III. UNCLOS III may aid the United States in ensuring that the naval ships and submarines can navigate freely along the high seas, that cargo ships and tankers may navigate along the world's sea lanes, and that the United States retains control over the resources found in the deep sea.237 As long as the United States remains a nonparty, it will not be able to rely on the protections provided by UNCLOS III.

The US is, of course, the world's sole superpower and its pre-eminent maritime power. Accordingly, the US clearly plays a leading role in global affairs. The US also perceives itself to be a world leader and is keen to project and promote this image and reality. The fact that the US is not a party to the Convention undermines that leadership role in the maritime sphere. Critically, when the United States comments on maritime issues of concern to it, such as regarding excessive maritime claims through the FON program or on the South China Sea disputes for instance, a frequently raised objection to Washington's interventions is that the US has not signed up to UNCLOS. This serves to compromise the credibility and authority of the US in global ocean affairs. US accession would therefore remove a somewhat irrelevant, but far from unimportant barrier to the United States playing a strong leadership role as the contemporary law of the sea. The counterpoint here is that by choosing not to participate the US is abdicating or at least undermining its credential to a leadership role in international ocean affairs. The rationale for ratification on this front alone is therefore, it is submitted, persuasive.

We will stabilize the outer permissible limit of the territorial sea of other nations at 12 nautical miles." We will gain the leverage to combat effectively excessive territorial sea claims and other excessive claims. At present, there are over a hundred excessive claims throughout the world.' These are notjust rogue states making these claims. Many, including those pertaining to the continental shelf, are from friendly nations or nations with whom we need principled, cooperative relationships. Our status as a nonparty to the Law of the Sea Convention hobbles our efforts to address these claims in an effective manner.

Specifically, I point out the counternarcotics area. There are excessive territorial sea claims that cause significant operational impediments for us on a daily basis. Our status as a nonparty makes it difficult for us to achieve effective operational agreements with those nations that have claims of territorial seas of up to two hundred nautical miles.

Next, Rear Admiral Frederick J. Kenney presented the importance of UNCLOS to the U.S. Coast Guard. He emphasized that on a daily basis the Coast Guard’s operational officers rely on the freedom of navigation that UNCLOS attempts to preserve. The Coast Guard is the only U.S. surface presence in many parts of the world, and this widespread presence allows the Coast Guard to respond quickly to international incidents. For example, a Coast Guard cutter was the first U.S. presence in Georgia after Russian troops entered the country in 2008.

Because the United States is not a party to the Convention, however, Rear Admiral Kenney explained that the United States cannot use its dispute resolution mechanisms for resolving conflicting claims to ocean territory. In one important dispute, the United States and Canada disagree about whether Passamaquoddy Bay is part of Canada’s internal waters and thus whether Canada can block passage of commercial shipping through the bay to East Port, Maine. If plans for a liquid natural gas (LNG) terminal in East Port move forward, Rear Admiral Kenney predicts this dispute will intensify without any clear means of resolution.

Rear Admiral Kenney drew on his personal experience as a negotiator to discuss the difficulties the United States faces in negotiating other treaties because it is not a party to UNCLOS. As the primary regulator of U.S. shipping, the Coast Guard participates in treaty negotiations with the International Maritime Organization (IMO). However, the IMO’s primary treaties are inextricably linked to UNCLOS, and Rear Admiral Kenney opined that the United States loses credibility in IMO negotiations because it is not a party to UNCLOS. Further, Rear Admiral Kenney suggested that bilateral agreements regarding drug enforcement would be easier to negotiate if the United States were a member of UNCLOS because they would be able to incorporate UNCLOS’ enforcement mechanisms.

Pages

The authors review the threat from China's aggressive claims in the South China Sea to the global maritime order and recommend a number of ways (short of ratifying UNCLOS) that the U.S. can "safeguard U.S. interests and raise the costs of further destabilizing Chinese behavior."

[ More ]