Underseas Cables

Quicktabs: Keywords

Whether UNCLOS can be used to address the mass surveillance carried out through the tapping of undersea cables is not entirely clear. To the extent that UNCLOS governs intelligence gathering activities, it could be argued that it only applies to intelligence gathering activities that take place within the mari- time domain, and will not govern the use of intercepts at cable landing stations. Further, if indeed mass surveillance can be done by physically tapping undersea cables by splicing the cable or otherwise, it is also not certain that UNCLOS is the applicable regime to govern such acts. Such surveillance does not fall within conventional perceptions of military activities/intelligence gathering at sea, which as mentioned above, is targeted, and aims at enhancing knowledge of the marine environment and/or the military capabilities of other State’s navies. That said, UNCLOS is of course a living instrument and subject to evolutionary interpretation, and for present purposes, this Article will as- sume that UNCLOS applies to the mass surveillance carried out by tapping undersea cables to the extent it involves physically tapping cables as they lay on the seabed.

In areas outside of territorial waters, namely the EEZ and the high seas, Article 113 applies. To recapitulate, Article 113 of UNCLOS requires States to adopt laws and regulations to provide that the breaking or injury by a ship fly- ing its flag or by a person subject to its jurisdiction of a submarine cable be- neath the high seas done willfully or through culpable negligence is a punisha- ble offense.217 While Article 113 could in principle cover intentional damage to the cable network, it has several limitations that render it ineffective at address- ing these threats. First, many States Parties to UNCLOS have not implemented their obligation under Article 113 to extend criminal jurisdiction over acts committed on the high seas or EEZ.218 The States that have implemented Article 113 are usually implementing their obligations under the 1884 Cable Convention; meaning their legislation has not been updated and the penalties are consequently woefully inadequate.219 The most common penalty in national legislation for intentional damage to cables is a monetary penalty,220 which is arguably not commensurate with the damage resulting from intentional inter- ference with cable systems.

Second, jurisdiction under Article 113 is limited to perpetrators who are na- tionals of that State, or if they use a vessel flying the flag of that State.221 Given the critical nature of submarine communications cables there is a strong argument that intentional damage is a crime that attracts universal jurisdiction and that all States should have jurisdiction over the offender. At the very least, the State(s) whose communications have been disrupted should have jurisdiction to prosecute as well as the State on whose continental shelf the damaged cable is located.222

Third, Article 113 only obliges States to adopt laws criminalizing intentional damage, and neither gives warships the right to board, nor arrest a vessel sus- pected of intentionally breaking a cable.223 Generally speaking, due to concerns about unnecessary interference with the freedom of navigation, the right to board vessels in areas outside the territorial sea (i.e. EEZ/high seas) is highly regulated under UNCLOS and is only allowed in certain instances.224 States have opposed a right to board without the consent of the flag states even for the suppression of the most serious crimes.225 However, there is some merit in the argument that warships of all States should have the right to board vessels suspected of intentionally breaking a cable. For example, Article X of the 1884 Cable Convention allows warships to require the master of a vessel suspected of having broken a cable to provide documentation to show the ship’s national- ity and thereafter to make a report to the flag state.226 This provides an effective deterrent to prospective attacks.

Given the likely economic and military impacts of cable breaks, the ability to threaten or protect submarine cables and their shore landings will be increasingly important in future conflicts. In a crisis, an aggressor could use multiple coordinated attacks on cables to compel an opponent to back down or employ them as part of an opening offensive to cut off the defender’s military forces from national commanders, intelligence data, and sensor information. Cable attacks could also be highly destabilizing, since they could prevent a nuclear-armed opponent from controlling and monitoring its strategic weapons and early-warning systems. In response, the country targeted could choose to place its nuclear weapons in a higher alert condition – or initiate a preemptive attack.

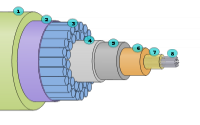

Tapping today’s fiber-optic cables is theoretically possible, but it is easier to cut or damage them and significantly impact the cables’ users. And while the exact location of cables is not publicly available, improvements to “bottom survey” equipment and unmanned undersea vehicles are making finding cables easier and faster. In time-sensitive military or diplomatic operations, the loss of communications for a few minutes or hours can be catastrophic. With financial transactions, the loss of even fractions of a second can cost millions of dollars as high-speed trades miss their targets and other transactions fail to go through or are lost entirely. The dozens of cable outages that occur each year do not cause a complete loss of service, but they do slow data-transfer speeds as information is re-routed through fewer intact cables. Most of these cable breaks happen in relatively shallow water, when rough weather moves cables around until they break or fishing trawlers catch a cable in a net. Some outages, however, have more nefarious origins. In 2013, three divers with hand tools cut the main cable connecting Egypt with Europe, reducing Egypt’s Internet bandwidth by 60%.

Repairing a submarine cable at sea is difficult and time consuming. First the break has to be located using built-in monitoring systems that can indicate the cable segment in which the break is likely to have occurred. Cable repair ships then must go to that location and pull up the cable until they get to the damaged spot. A new section of cable can then be spliced in, which can take several days to complete.

National economies now rely on undersea connectivity for a growing portion of their overall output. Today, essentially every consumer or commercial product contains commodities and parts drawn from dozens of separate countries in a “manufacturing chain” of subcomponent builders, product assemblers, suppliers, wholesalers, and retailers. These disparate players are able to seamlessly integrate their efforts using the Internet, enabling greater specialization and economies of scale within each step of the manufacturing process. This, in turn, promotes economic growth in countries that no longer have to either build an entire product domestically with great inefficiency or import it at high cost.

Global manufacturing chains and financial services are made possible by transoceanic cables, and more cable is being laid each year to meet the growing demand for bandwidth. The Asia Pacific Gateway cable, installed in 2014, transmits 55 terabytes of data per second (Tbps) – the equivalent of 100 computer hard drives – between East Asian countries from Malaysia to South Korea, funded in part by Facebook. Similarly, Google helped fund the installation of the FASTER cable between the United States and Japan, which will carry 60 Tbps, and is bankrolling a new 64 Tbps submarine cable between the United States and Brazil. Both content companies are hoping the new networks will increase their user rolls and reduce costs in underserved areas such as Southeast Asia, Latin America, and Africa. Data transmission to these regions with older cables can cost up to 10 times more than to Europe or Japan.