China

Quicktabs: Keywords

The possibility of China pulling out of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea has been mentioned in informal discussions among foreign affairs experts and observers but it was the first time that a Chinese scholar said it in public.

[ More ]

An ice-free Arctic will not bring more international shipping to Arctic maritime routes to and from China, the world’s largest market, according to a recent study by The Arctic Institute.

[ More ]

China has secured rights from the International Seabed Authority to explore and mine the seabed and is eager to begin mining operations but currently lacks the technological resources and expertise that its rivals possess.

[ More ]

The Arctic may contain 10-15 percent of the world's undiscovered oil reserves, with most of that oil located in the seabed of the Arctic Ocean. And China, thanks to its financial rather than military strength, could take the lion's share.

[ More ]

Japan on Saturday said it had won the rights to explore for cobalt-rich crusts in the Pacific, a move that could reduce its dependence on China for rare metals.

[ More ]

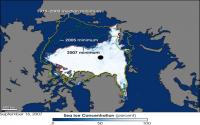

A combined team of researchers from the U.S. and China has projected, using a climate simulation tool, that the Arctic will become September ice-free sometime during the years 2054 to 2058. The group has published a paper describing their methods and findings in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

[ More ]

Recently China has been under withering political and legal attack for allegedly violating the 1982 U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea. What are the consequences if China simply gets “fed up” with the criticism and withdraws from the treaty?

[ More ]

China is rejecting the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) to settle disputes in the West Philippine Sea because Beijing knows its claim is not supported by the international law, a US naval expert said Thursday.

[ More ]

Senior Colonel Zhou Bo set China-watchers atwitter last week when he informed a group including Admiral Samuel Locklear, big kahuna of the U.S. Pacific Command, that the PLA Navy has "sort of reciprocated America’s reconnaissance in our EEZ by sending our ships to America’s EEZ for reconnaissance." One meme making the rounds among the punditry holds that Beijing has now conceded the U.S. interpretation of what sorts of activities are permitted in a coastal state's exclusive economic zone (EEZ).

[ More ]

For years, China has criticized the surveillance activities of U.S. naval vessels in its 200 nautical mile exclusive economic zone. Now China has begun, in however small a way, to do the same thing off Guam and Hawaii. And, somewhat counter-intuitively, this may prove to be in the interests of peace, stability and security right across Indo-Pacific Asia.

[ More ]Pages

An innovation of the 1982 UNCLOS Treaty was the creation of EEZs set forth in Articles 55 through 58.22 These zones ensure that coastal states maintain a significant degree of control over the natural resources off their coasts while retaining a substantial portion of the navigational and over-flight freedoms associated with the high seas region.23 Military ship and aircraft activities are not explicitly limited in the EEZ, so long as their activities do not involve exploitation of the resources resident in the EEZ. China sees the EEZ differently.

During development of the UNCLOS Treaty, Chinese delegate Li Ching made it clear that China did not concur with the EEZ concept. “China’s contention is that the essence of the new zone lies in the exclusiveness of coastal State jurisdiction. This contention explains why China repudiated the idea that the economic zone should be regarded as part of the high seas. If that zone were considered to be included in the high seas, so runs the argument, there would be no sense in labeling it as exclusive.”24 Not surprisingly, upon ratification in 1996 China asserted full sovereign rights over a 200 nautical mile EEZ.25 This assertion only adds to the complexities of the new EEZ concept.

The broader U.S. strategy for the South China Sea must follow three tracks. First, protect the rights of navigation for all through both diplomacy and demonstration. Second, work with the People’s Liberation Army Navy to help it recognize that China’s long-term interest in freedom of navigation is far more important to its national security than short-term efforts to control navigation in the EEZ. Third, promote regional resolution of jurisdictional claims over islands and seafloor resources of the South China Sea based on the principles of UNCLOS.

To this end, the United States must also recognize that regional influence depends not just on power but on its judicious application, as noted by Professor Barry Posen:

So command of the commons will provide more influence, and prove more militarily lethal, if others can be convinced that the United States is more interested in constraining regional aggressors than in achieving regional dominance.10

It is important to keep in mind that our friends and allies do not want to see the United States have an un- bounded role in the South China Sea. For them, UNCLOS is important in keeping U.S. involvement in balance with regional interests. If the United States fails to accept the convention’s obligations and limits as well as its rights, then its reputation, even with its allies, will be diminished.

In spite of President Reagan’s endorsement of the provisions related to navigation, the EEZ, and the continental shelf, the credibility of the United States as the champion of international law is weakened by its own failure to join UNCLOS. Joining would strengthen U.S. leadership at sea, and that will serve the interests of all parties in the South China Sea.

U.S. policy is, and should remain, to demonstrate and demand adherence to the rights of navigation and over- flight and promote regional resolution of issues of territorial and resource jurisdiction defined in UNCLOS. An important element of this strategy is for the United States to join the convention and re-establish itself as a champion of the international rule of law at sea while we enjoy the rights recognized by UNCLOS.

In attempting to increase its control and extend its authority throughout the South China Sea by applying domestic legislation to international waters, China has created a con- flict both with its neighbors and with UNCLOS. China’s claims are not just a threat to navigation in the South China Sea. They are a threat to the global commons and to in- ternational law that was developed to protect the rights of both coastal states and distant-waters states in those regions.

China’s efforts to enclose the local commons are short-sighted. It is growing into the role of a global power with its own interests in access and use of the global commons. In fact, the balance between coastal interests and distant- water concerns may now be in the process of tipping toward the latter. Gail Harris, writing in The Diplomat, stated: “Chinese strategists now also believe in order to protect their economic development they must maintain the security of their sea lines of communications, something that requires a navy capable of operating well beyond coastal waters.”9

The United States depends on support from ASEAN members to maintain effective operations in the South China Sea, so its responses to China must respect regional interests and concerns. While the United States is seen by the member states as a friend, they also know that U.S. interests are at times different from their own. The United States cannot take their support for granted. To do so may not just weaken joint responses to Chinese aggressiveness; it may put other multilateral maritime initiatives at risk, such as the Proliferation Security Initiative and anti-piracy resolutions in the U.N. Security Council.

ASEAN member states must be assured that the United States will provide a balance to growing power without becoming a threat to their interests. The United States can make this clear by emphasizing that its actions will conform with UNCLOS. As long as U.S. actions are compatible with and in support of the convention, ASEAN states will feel secure in U.S. maritime activities in their region, and China will know that there are limits that bind U.S. activities in the region.

While the credibility of the U.S. commitment to the convention is currently undercut by the country’s non- party status, this can be overcome by completing the effort of the previous administration to secure the advice and consent of the Senate to join the convention and then submit its ratification.8

Attributing motives to Chinese actions is difficult under the best of circumstances. In the South China Sea, it is even more so. Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Admiral Mike Mullen recently said that China’s “heavy investments of late in modern, expeditionary maritime and air capabilities seem oddly out of step with their stated goal of territorial defense,” while Secretary of Defense Robert Gates accused China’s top military officers of not following the same policy as senior political leaders who have worked to develop other aspects of the U.S.-China relationship.6

As a large and increasingly industrial state, China is concerned with matters of access to strategic and critical materials, especially oil and gas and industrial minerals. In the short term, China may give its regional interests highest priority. As it grows as a global economic power, however, it will find that freedom of navigation and over- flight worldwide are essential to its security.

Increasing dependence on sea lanes for imports of oil and minerals and access to export markets will push for a shift of priority on global mobility over control of the regional sea. A key reason for China to support UNCLOS is the “transit passage” provisions that assure the unimpeded passage of commercial vessels and the warships that are increasingly called on to escort them through the Straits of Singapore and Malacca, the Strait of Hormuz, and other chokepoints through which its critical imports flow.

Multiple examples of Chinese excessive naval claims that run afoul of UNCLOS Efforts to extend China’s control over the South China Sea run afoul of UNCLOS. Examples of China’s legal overreach include:

- Claiming that military aircraft do not have the right of overflight over the Exclusive Economic Zone: overflight of the EEZ is specifically recognized by the convention, and military surveillance is not limited

- Interfering with U.S. government vessels operating beyond the 12-mile territorial sea, notably Chinese interference with the USNS Impeccable and USNS Bowditch because they were “moving about in China’s Exclusive Economic Zone”

- Claiming that uninhabitable rocks in the Paracels and Spratleys are habitable so that China can claim they are islands with their own 200-nm EEZ, and engaging in military operations to take possession of the rocks from other countries.

Access and use of the global commons, particularly the sea and the air space, is a core element of U.S. military and commercial power. In times of war, control of the commons may be ensured by mil- itary means. In peacetime it is sought through international law and diplomacy and through lim- ited military responses when the rules govern- ing use of the commons are breached. In some cases, a peacetime incident may quickly result in a reaffirmation of traditional freedoms of the sea. In oth- ers, a more concerted effort, combining diplomacy with demonstration, is needed to return to adherence to inter- national norms. This latter combination appears to be the case regarding China and the South China Sea. As noted recently by Patrick Cronin and Paul Giarra:

Chinese assertiveness over its region is growing as fast as China’s wealth and perceived power trajectory. Beijing’s unwelcome intent appears to give notice that China is opt- ing out of the Global Commons.1

Though not a new phenomenon, China’s increasingly assertive activities in the South China Sea are drawing concern that the country is seeking regional hegemony at the expense of its neighbors in Southeast Asia as well as the United States, Japan, and South Korea.

China’s claims to those resources rest in part on his- toric claims illustrated in a map in which a series of nine dashed lines indicate some degree of jurisdiction over virtually all of the waters of the region (a similar claim has been made by Taiwan). With regard to U.S. naval op- erations, China has argued that the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) prohibits foreign military operations within its EEZ, a contention found nowhere in the text of the convention itself. China has raised the stakes by stating that control of the South China Sea and its resources is a core national interest on par with its claims to Tibet, Taiwan, and Xinjiang.

Yet Chinese claims are ambiguous. Does the nine-dash chart signify territorial claims to the South China Sea and the seafloor, or does it apply only to the rocks and their territorial sea within the marked zone? Are the claims really a “core interest,” or are they a starting point for negotiating the division of fishing and energy resources of the region?4

China’s arguments and actions reflect its regional per- spective and willingness to exercise its military in pursuit of regional interests. This is changing as China becomes increasingly reliant on distant sea lanes for access to stra- tegic and critical materials, particularly energy from the Persian Gulf, minerals from Africa, and recently, resources passing the Arctic. Security of sea lanes is now becoming a part of its strategic world view.

Of course, China’s withdrawal from the convention would weaken the reputation and authority of the tribunal and international law in general. It would also give notice that China is not to be trifled with — that it will not “be taken advantage” of by small Asian countries — some still influenced by their former colonial masters.

Unfortunately there is a long political history of world powers using, not complying with, or making new international law to further and protect their interests. Prime among these has been the U.S. Its refusal to join the 1982 Law of the Sea Treaty and the International Criminal Court, its withdrawal from the ICJ case, and its “invasions,” cyber and drone attacks, and interference in the internal affairs of other countries have certainly set a bad precedent.

The U.S. and its Asian allies need to be careful lest they push China into actually being what they fear most — a rogue country that uses might rather than right in its international relations.

Let us hope that China considers the costs of withdrawing from the treaty greater than the benefits.

The U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee has just approved a resolution condemning China’s behavior in Asian seas — behavior that China sees as defending its claims.

Meanwhile, rival claimants as well as the United States and other Western powers have criticized some of China’s actions in its 200-nautical mile Exclusive Economic Zone as violating the freedom of navigation. They and Japan say China’s drawing of enclosing baselines around the disputed Senkaku Islands (called the Diaoyu Islands in China) in the East China Sea is illegal.

China used to argue the “unequal treaty” doctrine regarding boundaries that were concluded with colonial or imperial powers. It is thus not surprising that its leaders occasionally revert to rhetoric reminiscent of that era proclaiming that this or that area is divine and sacred and has belonged to China since “time immemorial.”

Indeed some of China’s political analysts and particularly military officers seem to be questioning why China ratified the Law of the Sea Treaty in the first place. Part of the explanation is that China assumed — obviously incorrectly — that the Law of the Sea dispute settlement mechanism could be avoided by direct negotiations to settle maritime jurisdictional disputes.

China’s most significant and increasingly vocal critic is the U.S. This is of course ironic since the U.S. has not joined some 164 other countries including its allies in ratifying the treaty. Yet it persists in interpreting its provisions in its favor. Unwittingly the U.S. may be both showing China a way out of its dilemma and stimulating it to take it.