China

Quicktabs: Keywords

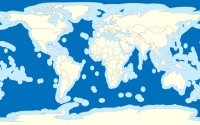

In response to China's aggressive claims in the South China Sea, the U.S. has been shifting its own focus to the legal domain. It is insistent that when it comes to maritime rights and access to natural resources, the law that truly matters is international law even though the U.S. position is significantly weakened by its non-party status to UNCLOS.

[ More ]

Chinese scientists have successfully retrieved samples from the seabed of China's polymetallic sulphide exploration contract area in southwest Indian Ocean

[ More ]

The US military carried out freedom of navigation operations challenging the maritime claims of China, Iran and 10 other countries last year, asserting its transit rights in defiance of efforts to restrict passage, a Pentagon report indicated yesterday.

[ More ]

China has said its research vessel surveying polymetallic deposits in the Indian Ocean has discovered two hydrothermal and four hydrothermal anomaly areas as the resource-hungry country stepped up efforts to extract minerals from the seabed.

[ More ]

After the US announced a new Arctic ambassadorship, Chinese media reaffirmed Beijing’s interests in the region.

[ More ]

Scholars these days are busy seeking to divine China’s intentions in the Arctic. Meanwhile, though, Japan and Russia have taken discreet – though decisive – steps to secure good relations and a better foothold in each other’s backyards.

[ More ]

For the first time, the United States government has come out publicly with an explicit statement that the so-called “nine-dash line,” which the People's Republic of China (PRC) and Taiwan assert delineates their claims in the South China Sea, is contrary to international law. The author considers next steps the U.S. can take to help resolve the South China Sea conflict, including ratifying UNCLOS to encourage consistency with the rule of law.

[ More ]

The author disputes the idea brough up in recent testimony that the U.S. could improve its bargaining position in negotiating a resolution to the South China Seas dispute by ratifying UNCLOS.

[ More ]

A huge chunk of modern-day technology, from hybrid cars to iPhones to flat-screen TVs to radiation screens, use dozens of different metals and alloys. What would happen if we run short of any of these valuable metals? Say there's a war. Or unrest in a crucial mining region. Or China decides to lock up its strontium deposits. Could we easily come up with substitutes? Or is modern society vulnerable to a materials shortage?

[ More ]

China’s status as an emerging player in the Arctic took yet another step forward yesterday as officials there marked the official opening of the China-Nordic Arctic Research Centre.

[ More ]Pages

As the Asia Pacific region continues to rise, competing claims and counter claims in the maritime domain are becoming more prominent. Nowhere is this more prevalent than in the South China Sea. Numerous claimants have asserted broad territorial and sovereignty rights over land features, sea space, and resources in the area. The United States has consistently encouraged all parties to resolve their disputes peacefully through a rules-based approach. The Convention is an important component of this rules-based approach and encourages the peaceful resolution of maritime disputes. Here again though, the effectiveness of the U.S. message is somewhat less credible than it might otherwise be, due to the fact that we are not a party to the Convention.

Some States in the USPACOM AOR have adopted deliberate strategies vis-à-vis the United States to try to manipulate international law to achieve desired ends. Such strategies are infinitely more achievable when working within the customary international law realm, versus the realm of treaty-based law. By joining the Convention, we greatly reduce this interpretive maneuver space of others and we place ourselves in a much stronger position to demand adherence by others to the rules contained in the Convention – rules that we have been following, protecting and promoting from the outside for many decades.

The dispute in the South China Sea is even more complex. Drawing on ancient maps and historical accounts, the Chinese and Taiwanese insist that the sea’s two island chains, the Spratlys and the Para- cels, were long occupied by Chinese fisherfolk, and so the entire region belongs to them. The Viet- namese also assert historical ties to the two chains based on long-term fishing activities, while the other littoral states each claim a 200-nautical mile EEZ stretching into the heart of the sea. When com- bined, these various claims produce multiple over- laps, in some instances with three or more states involved—but always including China and Taiwan as claimants. Efforts to devise a formula to resolve the disputes through negotiations sponsored by the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASE- AN) have so far met with failure: While China has offered to negotiate one-on-one with individual states but not in a roundtable with all claimants, the other countries—mindful of China’s greater wealth and power—prefer to negotiate en masse.

No region so rich in resources, both real and man-made, can avoid attracting the attention of China for long. Indeed, right on cue, Beijing has begun a concerted effort to make inroads in the Arctic—especially in Iceland and its semiautonomous neighbor, Greenland—with far- reaching geopolitical implications. In May, the Arctic Council granted observer status to China, along with India, Italy, Japan, Singapore, and South Korea.

China sees Iceland as a strategic gateway to the region, which is why Premier Wen Jiabao made an official visit there last year (before heading to Copenhagen to discuss Greenland). China’s state-owned shipping company is eyeing a long-term lease in Reykjavik, and the Chinese billionaire Huang Nubo has been trying for years to develop a 100-square-mile plot of land on the north of the island. In April, Iceland signed a free-trade deal with China, making it the first European country to do so. Whereas the United States closed its Cold War–era military base in Iceland in 2006, China is expanding its presence there, con- structing the largest embassy by far in the country, sending in a constant stream of businesspeople, and dispatching its official icebreaker, the Xue Long, or “Snow Dragon,” to dock in Reykjavik last August.

Thus it was striking to hear a Chinese military officer reveal in an open discussion at this conference on Saturday that China had “thought of reciprocating” by “sending ships and planes to the US EEZ”. He then went further and announced that China had in fact done so “a few times”, although not on a daily basis (unlike the U.S. presence off China).

This is big news, as it is the first time China has confirmed what the Pentagon claimed last month in a low-key way in its annual report on Chinese military power. Buried on page 39 was the following gem:

“the PLA Navy has begun to conduct military activities within the Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) of other nations, without the permission of those coastal states. Of note, the United States has observed over the past year several instances of Chinese naval activities in the EEZs around Guam and Hawaii … While the United States considers the PLA Navy activities in its EEZ to be lawful, the activity undercuts China’s decades-old position that similar foreign military activities in China’s EEZ are unlawful.”

It certainly does. And the Commander of U.S. Pacific Command, Admiral Samuel Locklear, who was present when the Chinese officer made the revelation, has now confirmed to the media that such Chinese operations are occurring.

To be absolutely fair and accurate, the Chinese officer did not say explicitly whether the Chinese ships (and/or aircraft) were actively collecting intelligence, or whether they were just venturing near U.S. territory to make a political point. But it would seem odd that they would forgo the opportunity to conduct surveillance. And he did say “reciprocating”.

Why is this revelation so strategically and diplomatically important? A few reasons. First, it amounts to a sign of a Chinese realization that its interpretation of the UN Convention of the Law of the Sea is not in its long-term interests. That interpretation has been that freedom of navigation does not include the right to conduct surveillance in another country’s EEZ. Most countries, including the United States, consider such surveillance to be a peaceful activity allowed under the convention. (To be clear, all including America agree that peacetime intelligence-gathering within the 12 nautical mile limit of anyone else’s territorial waters is a big no-no.)

America is the dominant hegemonic Power in Asia Pacific and possesses the dominant power projection38 capabilities in the region and seems committed to continue using them in a restrained manner.39 The littoral counties in the region, especially China, however, are developing the ability to deploy forces with the military capacity to threaten U.S. power projections. In particular, China‘s rapidly increasing economic power has caused widespread concern over China‘s ambitions to enhance ―blue water capability‖ for influence beyond its borders. These developments in China are of special concern to the US national interests, especially in the South-China Sea.40 In this regard, the recent statement by the Secretary of State Hillary Clinton41 in the ASEAN Regional Forum caused a lot of diplomatic tensions between the US and China. The said statement referred to the US interests in resolving territorial disputes off China‘s southern coast as ―a leading diplomatic priority,‖ thereby indicating the US intention to intercede in a region.

However, this is not the first time that the US has shown its interest in the maritime affairs in the Asia-pacific region, especially in South China Sea. The 2009 Impeccable incident is reflective of the US intensions to maintain its hegemony through power projections, even by circumventing the marine scientific research (MSR) provisions of the 1982 LOS Convention.

In the light of these observations, the US accession to the LOS Convention will have significant implications for the US interest in the South China Sea. Most notably, the LOS Convention would be applicable to the US completely as it does not allow making reservations at the time of accession. In addition, the US would be obliged to refrain from any acts that would defeat the object and purpose of the convention. Thus, by becoming a party to the Convention, the US would be constrained in the freedom to take inapt actions in the South China Sea without giving due considerations to its possible legal consequences. This may diminish the unchallenged naval power of the US in the Asia-Pacific.

While Arctic coastal states will play a dominant role in the Arctic, non-Arctic states that benefit from Arctic hydrocarbons and ice-free shipping routes will also seek a role. China, in particular, has focused financial, scientific, and political capital in the Arctic. As the world’s largest shipping nation, with 46 percent of gross domestic product40 derived from the shipping industry, China is aware that any changes to world shipping routes will have “a direct impact on [its]...economy and potential trade with respect to both imports and exports.”41 China is concerned that “the advantage of the Arctic routes would substantially decrease if Russia were to unilaterally charge exorbitant service fees for ships passing through its EEZ waters”42 and thus is advocating strong international cooperation within multilateral governing structures. In response to future Arctic opportunities, China has built the world’s largest non-nuclear-powered icebreaker, Xuelong (Snow Dragon), which has completed four scientific expeditions to the Arctic Circle to conduct oceanographic surveys and scientific research.43 In September 2010, the Polar Institute of China concluded an agreement on polar research cooperation with the Norwegian Polar Institute, to which China will contribute advanced instruments and laboratories, and will build a research center and a new ice- class research vessel.44 China has already engaged Canada in bilateral meetings to confront poten- tial issues that could arise from the changing Arctic environment; it is also eager to build relations with the Nordic countries in hopes of establishing cooperation between Chinese and Norwegian companies in extracting Arctic energy resources.

Finally, the United States should not ratify the UNCLOS Convention until the ambiguities regarding warship innocent passage rights and military operations in the EEZ are resolved. This is commonly referred to as the “military activities” exemption.59 President Reagan’s Executive Order made it U.S. policy to abide by the great majority of the Treaty, especially those sections germane to ship and aircraft navigation. The U.S. is therefore already in functional compliance. A case could even be made that the international acceptance of the Treaty -- even by those nations who have not ratified it -- has given the Treaty the force of international law.60

It is apparent that China does not intend to abide by the letter of the law -- at least not when it does not suit its purposes. Therefore, the U.S. must level the playing field in order to work through the issues. Ratifying the UNCLOS Treaty may actually take away the very flexibility that PACOM needs in dealing with China. Were the U.S. to ratify the Treaty tomorrow, the problems discussed in this paper would persist, but PACOM would have fewer “legal” options available under international law in order to respond to China’s excessive claims and provocations.

The differing views held by the United States and China over maritime boundaries has great significance for U.S. national security. The military forces of the United States provide a critical deterrent against foreign aggression that might affect the global flow of commerce. In order for U.S. forces to be a credible deterrent they must have access. In its analysis of the national security implications inherent in the UNCLOS convention, the U.S. Department of Defense emphatically stated that, “Assurance that key sea and air lines of communication will remain open as a matter of international legal right and will not become contingent upon approval by coastal or island nations is an essential requirement for implementing our national security strategy.”49 China’s policies and actions place this freedom at risk. If they are allowed to prevail in their claims, the negative operational consequences for USPACOM are tremendous.

If China is allowed to prevail in its claims of sovereign jurisdiction over enormous ocean areas, this would seriously degrade the ability of U.S. forces to conduct peacetime operations in a critical region. Not only would the U.S. Air Force and Navy be unable to operate in much of the south-east Asian littoral, but forces responding to contingencies in other regions could be forced to take alternate routes that would significantly restrict the ability of the U.S. to quickly respond to a crisis.50

Second, without U.S. presence, important partners such as Singapore and the Philippines would no longer benefit from the stabilizing influence that the presence of U.S. forces provides. Instead, as the emerging naval power in the region, Chinese ships would be free to exert their influence unchecked.

Lastly, any freedom of navigation operations conducted by U.S. forces take on a new level of risk as the mere presence of U.S. forces in China’s claimed EEZ could result in hostilities. U.S. forces and Allies, like Australia, routinely conduct freedom of navigation (FON) operations in order to oppose illegitimate maritime claims. These operations are not intended to be antagonistic. Rather, they are intended to serve as just one element in the discourse between nations.51 However, with China’s extreme sensitivity to sovereignty, most U.S. FON operations will almost certainly be viewed as blatantly provocative.52

In May 2013, five Asian nations—including China—were granted ob- server status in the Arctic Council, and China has stated it does not intend to be a “wallflower” in the forum.33 Beijing has expressed an interest in developing new shipping routes through the Arctic that will connect China with its largest export market—the European Union. To that end, in August 2013, a Chinese merchant vessel loaded with heavy equipment and steel set sail from Dalian en route to Rotterdam via the Arctic’s Northern Sea Route (NSR).34 China has also expressed an interest in developing Arc- tic resources. In March 2010, Rear Admiral Yin Zhou of the People’s Liberation Army Navy stated at the Eleventh Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference that “under . . . UNCLOS, the Arctic does not belong to any particular nation and is rather the property of all the world’s people” and that “China must play an indispensable role in Arctic exploration as it has one-fifth of the world’s population.”35 Officials from the State Oceanic Administration have similarly indicated that China is a “near Arctic state” and that the Arctic is an “inherited wealth for all humankind.”36 As a party to UNCLOS, the United States could claim an ECS in the Arctic and forestall any encroachment of U.S. ocean resources by China or any other nation.

In theory, the 1982 UNCLOS Treaty leveled the playing field and created an unambiguous set of rules for all countries to abide by. While the convention represents a major step forward in codifying many of the historical practices that had evolved into international law and crafted practical guidelines designed to promote equitable commerce, the contemporary practice does not yet mirror the theory.

China’s national defense policy declares, “China . . . defends and administers its land borders and seas under its jurisdiction, safeguards the country’s territorial sovereignty and maritime rights and interests, and secures both its lands and sea borders strictly in accordance with treaties and agreements it has signed with neighboring countries, and the United Nations Convention on Law of the Sea.”12 In reality, however, Chinese practice with regard to innocent passage, exclusive economic zones, and sovereignty claims over what China calls “Historic Waters” is largely inconsistent with UNCLOS.